Question

From the original questioner:

I am looking for a faster way to make beaded faceframes. Presently, we apply the beadmould after assembling the faceframe. Works okay, but takes lot of time.

I would like to run the faceframe parts (stiles and rails) through the shaper to form the beadmould before assembly. Only problem is coping notches in the stiles for the rail joints. I wonder if anyone has a fast, simple way to do this?

Forum Responses

(Cabinetmaking Forum)

From contributor A:

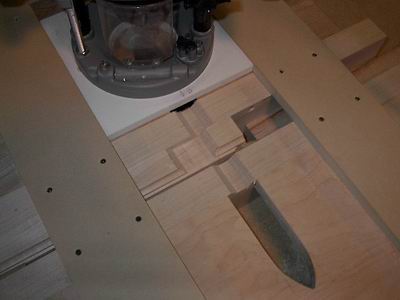

We do a fair amount of beaded frames and we cut our beads on the shaper and then cut the joints on the table saw and the slider. It?s not too terribly time consuming because then we pocket screw the frames together. I know for a fact it?s way faster than adding the bead afterwards, plus it?s a better looking job. Here?s a picture of a cabinet in our office kitchen.

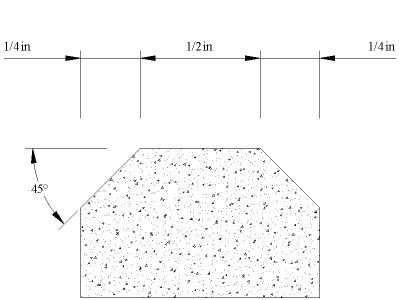

I've settled on using a Japanese handsaw with a big 45 degree angle guide block made from 6/4 scrap. Basically, I cut all the miters on my layout lines. Then I cut the bead off with the tablesaw.

The midrails I simply knock the bead off with a sharp chisel. We all get into the habit of trying to set up machines to make things go faster, but in reality I can cut a kitchen's worth of miters in less time than I can set up the machines. Don't forget about those chisels, planes, and handsaws.

As far as hand cutting goes, I could see doing it that way myself, but I do not have much time to actually be in the shop these days. It takes a pretty skilled employee to lay out and hand cut the joints. I find it really hard to get help with that level of skill these days.

I like the idea of using a router and jig, and would like to know more about it. What kind of bit are you using in the router? Is tearout a problem? Have you worked out a stop system or do you hand mark the parts?

We could easily justify the morso chopper that Hoffman sells, but I would prefer to stay with what I have or else cause a real haunching machine to be produced.

The Hoffman system is better than what I currently use but still has, in my opinion, several weaknesses. The quality of the cut seems to be different on the front of the frame than it is at the back. While you only see the front of the face frame you still have to sort out mirror-image indexing to keep the left and right sticks presenting the same side to the guillotine.

When these machines are demonstrated at the shows, the blades are very sharp and the samples they produce are out of luan lumber. Take a piece of eastern maple to the show next time and try to figure out how long that blade will hold up.

The system we currently use is one that Derek Slotemaker told me about. I mentioned a magic molder head during another thread regarding the beading. We have a magic molder set up in a dedicated tablesaw with a crosscut sled. Our sled is actuated on linear bearings but you could almost do this with not much more than a miterguage.

Like I said, we do a lot of these frames. Our current cost structure is about 25% of what it used to be. I can envision systems to reduce our current costs by half.

We've had this setup in operation for a couple (maybe three) years now. I did buy a backup set of knives but have not yet felt the need to change them.

There are a lot of nuances in carbide today. The alloys that are used in a lot of insert tooling can differ from what you might find on brazed tooling. The initial sharpness and longevity vary a lot from manufacturer to manufacturer.

A lot of this has to do with porosity of the steel. Think of a highway that is brand new and one with potholes. The deterioration starts at the edge of the pothole. This is where the asphalt has got a spot to crumble into itself.

Steel is like that highway. It appears to be smooth but under magnification has small pits. Advances in metallurgy have produced alloys that flow better into these pits, thus producing an edge that will hold its initial sharpness longer.

I would not say that the magic molder is the end-all solution. It's a big step up over the tablesaw and router and it only costs a couple of hundred dollars. I think the Hoffman system is probably a better system but not twenty times better.

Put another way, if I had to spend the dollars again I would rather have a second tigerstop in my assembly zone than the incremental utility of the Hoffman over the magic molder.

a) Cost: The basic manual NFL notching machine sells for $5,170.00, the larger NFXL model for $6,240.00. You can purchase the machines individually and use pocket screws or dowels, or in machinery packages to use our Dovetail Keys for the connections.

b) System weaknesses: The machines have a nylon chip breaker mounted flush with the tabletop to avoid tearing on the underside. Adjusted correctly, the backside will show little, if any, tearing. The top or face side of the moulding will always have a very clean cut.

Mirror indexing is a simple and accurate way to produce straight frames. You'll mark and completely notch the first stile, then flip it upside down and use it as template to set-up the stops for the opposite side.

c) Knife sharpness and wood species: Of course we use clean, new machines and knives for our demos, but I can honestly attest that over the last 2 years we have sold a good number of manual notching machines, and so far we've received less than 5 sets of knives back for sharpening! If the knives are just tired but not nicked, you can even re-hone a micro bevel with a fine stone yourself.

By the way, we have never used luan for samples. In the past we've used birch, oak and maple. I have made samples in hickory, rock maple, teak and even MDF for customers, with the same clean results.

If anyone would like to see results in different species, please bring your material either to one of the shows we attend or send us samples. We'd be happy to machine the moulding and return it for your evaluation.

Comment from contributor I:

We also make these beaded inset style cabinets. We run the bead on the face frame stock, chop the notches and miters with a Morso-FC chopper, and assemble with pocket screws. We made fixtures for the chopper so the width of the face frame stock doesn't matter and one has a stop to aid the corner clipping process. You can also do this machining with the old 2 knife miter chopper with a secondary task with a router table to clean up the notch.