Question

I am trying to find the simplest construction method for making frameless cabinets using the 32mm system. I have been making solid wood cabinet doors for three years and I have an opportunity for the cabinet units. I need to start with minimal tools and jigs. Also, what would be the best method for joining panels; biscuits, dowels, dado? I am concerned about not getting a correct alignment with the panels. Any suggestions would be appreciative.

Forum Responses

(Cabinetmaking Forum)

From contributor Y:

Your question is open ended. Answer as asked would be yes, yes, maybe, sometimes, I don t see that you would often have a need to be joining panels that is to simply make larger panels. That is if weíre talking residential cabinetry. The True 32 system is just one guy(guys) technique for setup and execution of frameless work. In cabinet making the two simplest things one can build are euro cabs and cutting boards but I forgot which order those were in. Good luck with it and dive right in.

If you need deeper than 24" cases I'd recommend a 21 or 29 spindle machine. I build residential so 19 spindles don't hinder me much. The last two houses I did, I used doweled finished ends, but will probably use applied ends and raised panels from now on. I assume you have the edgebander and line boring machine already, preferably double row for hardware.

The Blum system is a great place to start. They have a free technical manual explaining it. If you read and study all these things then spend a year scratching your have and cussing a lot you will come up with your own hybrid system that suits your process.

You guys that swear by stapling, gluing, and screwing are not seeing how dowel construction affects the entire process. Someone said it will "add a process" that is wrong, by my calculations it removes several processes. Most the processes is removes are ones that require the worker to manually align and secure the box. Dowels eliminate that. The advantages are in the small details that are not so obvious if you have not worked in a Euro shop. The worker does not have to slip clamps over unsecured parts (a difficult balancing act that must be mastered), dowels allow you to simply mallet the parts together then slip the clamps on the already stable and sturdy box. While I am already finished tightening the clamps and gluing the back, the "screw and glue" guys are walking around the box and stapling.

Another huge factor is material choice. You simply cannot glue and staple melamine. If your process requires the use of plywood you will have lots of other time consuming issues to deal with.

But the claim that dowel construction is faster than staple and screw (no glue required) can be very misleading. In a vacuum, where everyone is making frameless cabinetry with the same level and type of equipment, and utilizing the same production systems, you might be able to actually test this claim effectively.

But we are not in a vacuum, and everyone does not have the same level and type of equipment, nor the same production objectives. Some have minimal equipment, others have very expensive manual equipment, others have semi-automated equipment (NC) and others have highly automated equipment (CNC). Even the highly automated shops can be very different in that some prefer nested based manufacturing on a CNC router, and others prefer cellular systems utilizing a beam saw and a Point-to-Point CNC machining center.

Some prefer batch and queue production systems, others prefer one piece flow production systems, and machine times can vary greatly between companies with these differing levels of equipment, and different production systems. If you prefer a batch and queue production system (cut, machine, process), and your objective is to machine and assemble a bunch of boxes with as few people as possible, and you donít have a lot of ancillary processes that need to co-ordinate with the box production, then dowel production is probably a good fit for you.

If you prefer a one piece flow manufacturing system, or small process and transfer batches, and your objective is to turn out a few cabinets a day with a lot of ancillary parts that blend with these boxes to make up the end product, then dowel construction might actually slow you down.

To add an additional machining process to every single structural horizontal part (both ends of each part) and every single vertical part can take a lot of extra time, and you absolutely have to consider that material thickness variations can make this fool-proof system less than fool-proof. To have to add dowels and glue to every hole takes time that many seem to discount as trivial, but it can be comparable to the time it takes to staple and screw. The primary attributes of dowels is to locate/align parts and to eliminate the need of applied end panels. For the parts that align with an edge, either is easy (dowels or staple and screw), for the parts that are positioned at random locations within the cabinet like mid rails and fixed shelves, the dowel machine has to be setup for that position, and is just a likely to be right or wrong as manually marking the position. For a nested manufacturer, these can be located and aligned using blind mortise and tenons, or with simple location lines drawn with a veining bit (there are effective alternatives to dowels for location and alignment).

In one piece flow environments, to add the additional boring step can add considerable time to the machining process, and could potentially remove the ability to balance the flow (equal process times for the other steps/areas). The case clamp time, no matter how short can disrupt the flow, if not at the TAKT level, at least in the ramp up stage of restarting the flow after a disruption (to ignore disruptions is tantamount to setting yourself up for failure in the commercial and residential cabinet manufacturing business). Our industry is ripe with internal and external potential for disruptions (i.e., job delays, material delays, MIA employees, etc.), and to not account for those inevitable disruptions in our manufacturing systems can be painful or even fatal to our business.

We only have two viable methods to account for disruptions, one is to buffer with inventory (raw, WIP and finished), the other is with excess capacity (our ability to sprint). Both come at a cost, but one affects our ability to remove waste from the process more than the other, one lowers our sprint capacity significantly, so pick your poison carefully (just because you can manufacture 20 cabinets in a day does not mean you can manufacture 5000 cabinets a year). Disruptions are inevitable, but how we deal with them can make all the difference in the world. The bottom line is that we are operating in a world of dependant events, and to make decisions without understanding the far reaching implications of those dependencies can have a dramatic effect on our ability to make more money now and in the future.

The third hole and cam of the Minifix only make them viable when you need a fastener free end panel and need two sided mounting (e.g. on a shared panel) and/or need to assemble the box in place on site. The Mod-eez pocket is more involved than the Minifix cam hole, but endboring (32mm offset) is optional and itís an invisible fastener with other uses.

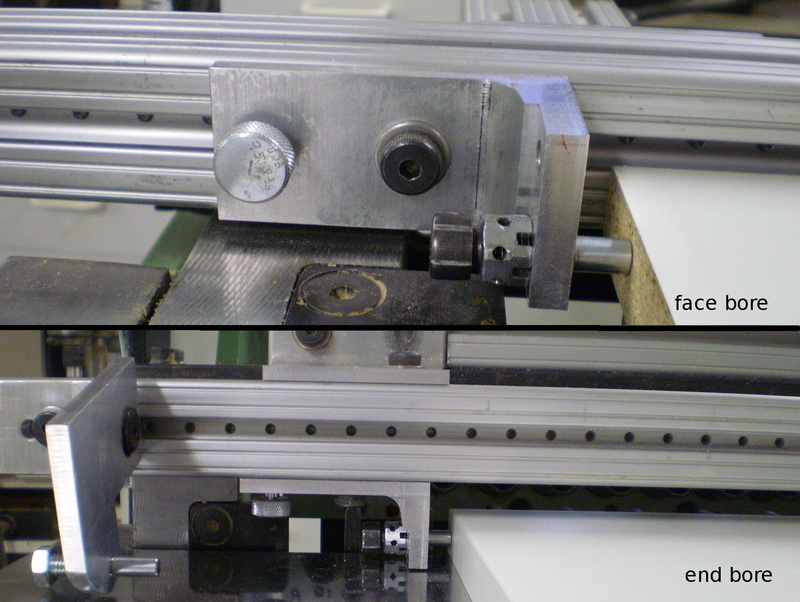

With minimal tooling, the only apples-to-apples comparison to staple-and-screw is confirmats. If you are setup for endboring (i.e. need/use any of the above), confirmats are the best choice. Parts easily and accurately align during assembly (always endboring inside up allows for variations in material thickness). Confirmats make it easy to index any and all components, e.g. stretchers/rails indexed to system holes. There's no free-handing, no measuring/marking and no blowouts.

To insure that the front edges are flush, each joint needs to be bored from the same reference point (stop or fence), i.e. the edge-banded edge always goes against a stop or fence (not in my mind when I did the picture). The circle is complete because the only way you can do it is with inside up end boring and inside down face boring.