Compound Curved Veneered Panels

Theoretically, it's impossible (or "impractical") — but hey, we can dream. January 20, 2010

Question

Has anyone done compound curved veneered panel work on this scale? Parquetry or solid veneers?

Forum Responses

(Architectural Woodworking Forum)

From contributor R:

We will need more info. What size panels? What radii compound curves? What "scale" are you referring to?

From the original questioner:

I'm not asking if there is anyone out there who can do this for me. I am curious if anyone has done this work on any scale.

From contributor D:

It is rare to see much of this since wood won't bend both directions since it has such a high modulus of elasticity - no stretch.

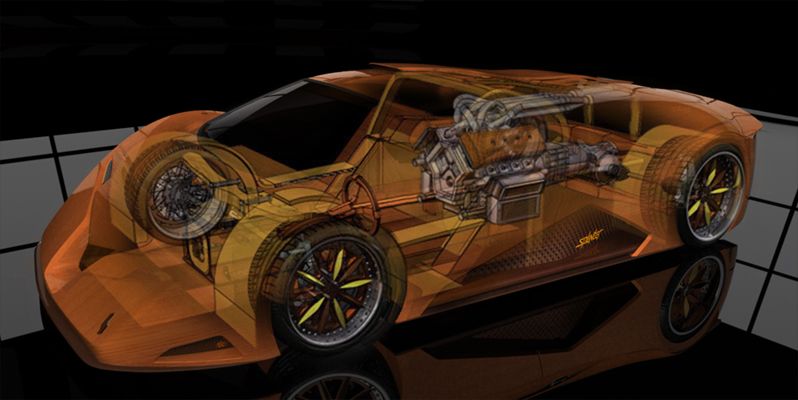

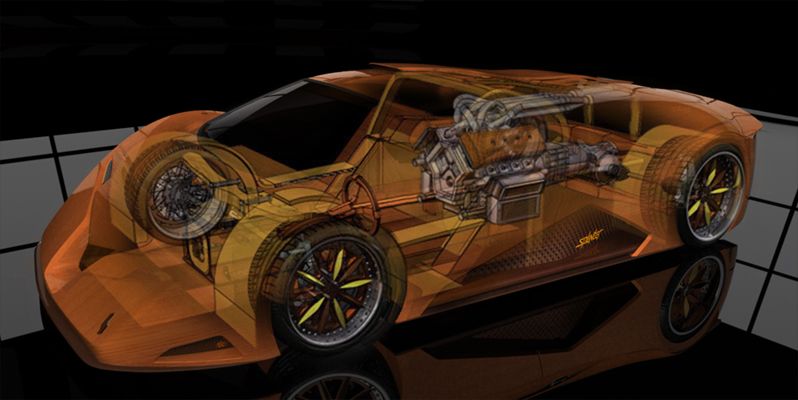

There are two examples. Veneered "raised" panels in commercial doors that have a mild cove raise are veneered with a membrane press. There is a slight compound at the corners, and a frequent cause of failure in production. I do not know if the veneers are different from the usual before pressing. A second example is seen in the clever use of woven veneers to make compound curves in the wooden supercar with the unfortunate name of "Splinter." Not applicable in any typical application, but clever nonetheless.

Photo courtesy of Joe Harmon Design

Click here for higher quality, full size image

From contributor B:

To the original questioner: Is the car example what you are talking about? That is, trying to veneer the surface of a sphere?

From the original questioner:

Wow. That car is what I am talking about. I'm only curious because I am taking a class from Brian Newell and I am hoping to use these techniques in high end bathroom vanities, bars, and kitchen islands. As far as I can search there is no evidence of this work yet being implemented in architectural millwork and casework. I was hoping there might be some experience to bounce off methods of pushing the limits of what wood can do, and ways of getting around what it can't do.

It looks like they used a fiberglass substrate and laid up veneers over individual components. That's very cool. Thanks for sharing.

From contributor D:

A third example of compound veneers and second example of woven technique is the old teak (?) salad bowls, circa 1960 or so. I heard they were woven sheets impregnated with the same resins as HPDL (Formica, et al), and pressed with heat to set the resins. Durable, dishwasher proof, attractive and economical, these have vanished from the scene for some reason.

Flat veneers are very limited in their compound-a-bility, and woven is an improvement. To do a sphere as BH Davis suggests would be near impossible with flat stock, unless the sphere were to be very large.

Newell's work looks like it has gentle compounds, some look woven and some look pieced. Pieced veneers can be individually shaped to more easily conform to compound surfaces.

From contributor N:

There are guys here in Charlotte that do this stuff. I don't think Mr. Zepsa would appreciate them sharing on the web however...

From the original questioner:

Brian doesn't do any weaving. That is a new concept to me. I don't think I would like the texture of that personally. I don't think Mr. Zepsa is using any of the same techniques as Brian and the people that work under him with their own spins on what he's doing. The curves are somewhat mild, but push the limits of the wood.

Also, I'm not sharing Brian's techniques over the web. I don't think he'd mind conversation over the concept.

From contributor I:

Here's a related job at the Project Gallery:

Sculptural Flooring

From contributor L:

I have a couple of young guys working for me that make compound curved skateboards here in their off time. They do not have extreme compound curves, but make neat looking thin, strong boards. They've been after me to allow them to use our equipment to manufacture boards to sell. They can play for themselves here, but if they want to go into business they need to get their own setup.

From the original questioner:

I'm checking to see if either commercial or residential custom shops are using this (i.e. bars, islands, large scale jobs other than pieces of furniture).

From contributor N:

Boatbuilders build in compound curves - it's all they do. The book "Gougeon Brothers on Boatbuilding" is a great reference out of the hundreds of books on boatbuilding out there. I think you'd find their techniques of some interest if you are not already familiar with this book.

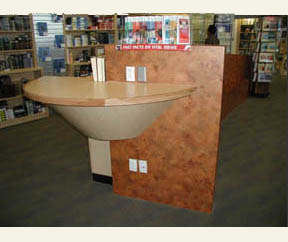

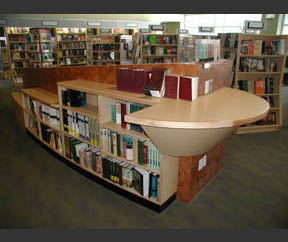

From contributor C:

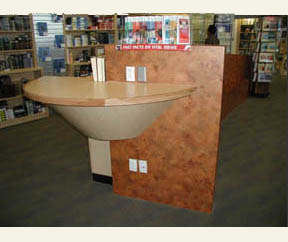

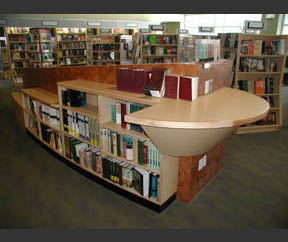

We do compound curves such as conical sections fairly often - one of my engineers has got the unwrap function in Microvellum pretty well mastered so we can take an odd shaped elevation, unwrap the skin and send the result to the router for an accurate cutout. We have done odd convex and concave shapes as well, sometimes with good math, sometimes by trial and error.

Projects designed by Dekker Perich Sabatini

From the original questioner:

That kind of looks like a cone shape, and not curving in two directions (like a football).

From contributor O:

I didn't really think a cone was a compound curve, but here's an elliptical one I did.

Click here for higher quality, full size image

From contributor D:

I use the term "compound curve" to describe a surface such as a football or auto fender. I have no idea if this is the proper term, but I have heard others use it also. Mostly as something to not get involved with.

Today, we do compound curves as casings for curved head (elevation) doors/windows in curved (plan) walls. Also domed ceilings to circular rooms. This work is rarely veneered, typically solid woods. Our curved stairs also require compound curves of another sort - this we refer to as twisted work, since it is described differently from two radius work (as in the window casing example).

The work we do all has one plane flat at any point - if that makes sense - so is not like the surface of a football/fender. A curved stair stringer with a pitch change will have a more complex curve at the top of the skirt/curbwall, but still not like a football.

From contributor B:

We occasionally do a radius top door or window in a curved wall. I call this a compound curve. When we do spiral stair rails or stringers I call these spiral or helical curves. If the original post refers to a part of a sphere, then I don't think either of these examples apply.

In both the above cases if you look at any given point along the curve you can lay a straight edge down in some orientation and it will touch end to end. You can also create a wide panel out of wide material and it will conform to the shape. You just laminate along the primary curve (such as the wall surface) and cut (such as on a bandsaw) the secondary curve (top/bottom of panel, etc.).

This is not true if you are trying to laminate a car fender or a sphere, though. In those situations there is no point at which you can lay down a straight edge and have it touch full length. Don't know if this helps clarify things, but hopefully it won't muddy the waters.

From contributor P:

As contributor D stated earlier, wood does not stretch; sheet metal does. This doesn't seem practical.

From contributor B:

Thinking about this a bit more I'll add to my previous post that veneering a cone would fall into the same category as my compound or helical curve. That is you can successfully lay a straight edge on the surface.

I don't have much experience with veneers so will assume that stitching is like in sewing... bringing edges together. At first I thought that you couldn't cut a piece in a pattern that would lay down on a spherical surface. Then I remembered the example of a map of the world being glued onto a globe. Those curve edge fingers come right together. Even though any point within a given finger is an area that has to conform to the surface, apparently there is enough elasticity in the paper to make the bend around to match the globe surface over that small area. I suspect the same would be the case with veneer.

Hey, now a marquetry globe - that would be something to see!

From the original questioner:

Yes, compound curves are like fenders and footballs. Some of the examples shared are tapered curves that do not bow out like a barrel. I have in the design phases, and I have been working with Brian Newell in his shop learning a process to achieve this kind of work. I don't think there is a whole lot of aesthetic appeal in extreme curves in furniture. I like subtle, gentle, fair, sweeping curves. Wood will compress easier than it will stretch. It will stretch to a slight degree, but will split or crack easily as we all know. Which is why this seems impractical. The word "impractical" seems to pop up a lot in this work because people tend to want to avoid the head scratching and repeated failures until success. I personally enjoy pushing the limits and exploring the capabilities of what we can do in our work. It's why I am curious to see what people are doing out there.

From the original questioner:

Thinking about this a bit more, I'll add to my previous post that veneering a cone would fall into the same category as my compound or helical curve. That is you can successfully lay a straight edge on the surface.

I don't have much experience with veneers, so will assume that stitching is like in sewing - bringing edges together. At first I thought that you couldn't cut a piece in a pattern that would lay down on a spherical surface. Then I remembered the example of a map of the world being glued onto a globe. Those curve edge fingers come right together. Even though any point within a given finger is an area that has to conform to the surface, apparently there is enough elasticity in the paper to make the bend around to match the globe surface over that small area. I suspect the same would be the case with veneer.

Contributor B, now you're talking! It's called relief cuts. You can do test runs with thick paper to predict what the veneer will do. You can orient your design to defeat the problematic areas. It would be really tough to nail such a project as a globe. I would go for a parquetry technique to do that. It would be funky with the relief cut method if the grain did not match up well and you did not nail the seam. Gaps are not pleasant to look at. Piecing it together by means of parquetry, possibly laid up in sections as opposed to all at once is a manageable solution.

From contributor U:

A cone is not a compound curve.

From contributor Z:

Surface model the form in Rhino or Mathematica. The wire frame coordinate system will give you some idea of where to splice the veneers.

From the original questioner:

I am uneducated with all computer software programs. I'm going to Humboldt State University to obtain my BA in Industrial Technology with my focus in design. I really look forward to using modern technology to help with building forms. Some shapes you just can't get rough sawn even in a 36" Oliver prior to application of veneers. CNC and fiberglass molds will enable repeatability on a much more efficient scale.

From contributor K:

Brian Newell is the best designer out there as far as I am concerned, so congrats for getting to study with him. Will you be going to his shop, or is he back in the US for your class?

I have done some bending of parts using compound axis bends, which did some surprising things that I liked, and should have revisited. I made a desk for Hillary Clinton, back when Bill was Governor of AR. I don't think I have any good digital images of the back to share.

The desk had a console suspended over the desktop, which had a long bend, end to end, let's call that X axis, which was slanted back about 20º with more bend at the top than the bottom, which would sort of define a section of a cone, Y axis. Both ends then had a hollow curve on the opposite axis, Z. When I forced the cross axis bend into the three or four layers of 1/16" ply, which I had previously laid up flat, the middle took on an outward bulge just opposite direction from the hollow.

I had already made the top, bottom, and sides of the console, which were through dovetailed and dry-fitted together - that is what I used for a form to clamp the bag up against. I used epoxy as the adhesive, and as stated above, the form was outside of the bag. Thickened epoxy is excellent for this kind of bagging, in that it is so slippery, and slow setting.

If you are just exploring ideas, I would suggest that you get or make some thin plywood, then start bending it into shapes, contorting it to see what you can get. If you can get shapes that you like this way, the face pattern is already taken care of while it is flat and easy.

From the original questioner:

Brian is actually living in Fort Bragg, CA now with his 2nd shop setup. He goes back and forth to Japan now and then. I may go on a lumber buying trip to Tokyo in January.

My first project is going to be a barrel front/side/back desk in either mahogany or Bubinga with pear interior. Got the design basically established and will have a lot of cross bonding laminates over a large form. If I can't get my form sculpted from rough band-saw and hand planes I'll outsource it to a CNC out of solid MDF. Would be super heavy, but whatever it takes. This kind of work is impractical for some, but for others willing to endure the process it can be very rewarding. I'm looking forward to it.

From contributor K:

Here is a piece that is solid, coopered and carved that you might like.

The following images courtesy of artist Keith Newton, photographer Mark Mathews, and WoodCentral.

From the original questioner:

That is an impressive piece. Neat door lift hardware too. Solid work is fun to sculpt. I bet the fitting of the sides to tops and bottom was fun. Did you dowel the carcass? Did you bend the brass knife L hinges or did you have them cast? I'm very glad to see other examples of this work being utilized, especially quality examples.

From the original questioner:

Okay, I had a moment to take a look and answered all of my own questions. Very detailed and informative page. I like your door lift hardware concept.

From contributor K:

Thanks. The door lift hinges were sawn from 3/8" plate brass which I found at the scrap-metal yard. I did it all in my shop using my bandsaw to cut the shapes. Then sanded and polished the edges with some of my woodworking equipment that will work metal as well as it does wood. The joints between sides and tops and bottoms are all M & T. Yes, the side doors are bent L pivot hinges.

From contributor M:

Quick and dirty... Don't underestimate the power of edge set!

Click here for higher quality, full size image

From contributor M:

Nice bar. I like the I-beam arm rest. Do you build bars often?

From contributor M:

About one per year... Otherwise, it's cabinetry and furniture. Thanks.

From contributor L:

I like the bar. Nasty steel corner, though.

From contributor M:

Yeah, man! "Chocolate and Cigarettes."

From contributor V:

Look at antique mantel clocks. The frame that holds the dial or the glass over it is often about 1/3 of a rod in cross section and veneered. Now that's a compound. I don't know how the old timers did it. I did reveneer one. The veneer runs in a starburst-like pattern across the profile of the frame. Before glue-up, the veneer would not lay flat on the table, because of the change of measurement from inside profile to outside. I played with it for a few hours before I got it right. Glued up with vacuum.

From contributor M:

A great demo of what can be done with vacuum is the video put out by Darrl Keil of Vacuum Pressing Systems, Inc. Actually there are two videos (my copies are old so they are probably updated now to DVD.) One of the things he shows is veneering a round tabletop with what looks to be about a 3/8" radius edge then about 3/8" of vertical flat all the way around the top. It's all done with a flat piece of veneer. He also veneers crown molding. Not that that is a compound curve, but still tricky. Worth their price.