Controlling Drying Conditions and Monitoring Progress

Here's a lively, sometimes contentious, and very informative thread about how to ensure quality control when drying lumber in a variety of different kiln types with different control systems and instrumentation. July 16, 2012

Question

Drying a green load of northern 8/4 red oak. Does anyone have a good schedule to use? I have never dried a load of 8/4. Any helpful hints?

Forum Responses

(Sawing and Drying Forum)

From Professor Gene Wengert, forum technical advisor:

There is none better than what is in DRYING HARDWOOD LUMBER and DRYING OAK LUMBER. You using a DH or steam? No.1 Common and Btr? Green means "tree green?"

Drying Hardwood Lumber

Drying Oak Lumber

From the original questioner:

Thanks. Steam kiln, 1C&BTR lumber and the material will be green.

From Professor Gene Wengert, forum technical advisor:

Make sure the controls are accurately indicating and controlling the RH or EMC. Drying samples to measure daily loss are essential. Drying time is no less than three months. Shed drying is less expensive above 35% MC.

From Professor Gene Wengert, forum technical advisor:

Watch the lumber's behavior. For that reason, I developed the drying rate concept 30 years ago where we watch the drying rates rather than just RH and temperature. It makes sense to watch the lumber's behavior rather than an instrument, especially because the instrument does not know the air flow. Even when monitoring rate, I still will get a question where the operator wonders if the load is okay even though his samples are checking.

In any case, correct sampling procedures must be followed, per the book. The schedules in the book, developed over 60 years ago, have been successfully used on billions of BF of red oak. Of course, the schedules are just one part of the overall process. Operator skill is also important. I tried to put all these facts together, plus my 40 years of experiences, when I wrote DRYING OAK LUMBER and also DRYING HARDWOOD LUMBER.

From contributor D:

I don't know how you guys can put up with those steam kilns. I can load 12/4 red oak into a vacuum kiln, push the start button, and come back to perfect wood two weeks later. No checking samples. No checking the kiln. No adjustments. Red oak is so easy!

From contributor K:

My intent was not to start an argument about how to dry oak. You cannot dry heavy oak simply by referring to a schedule no matter where it came from. It takes a lot of input for every little change that you make because, as anybody who has dried heavy oak commercially knows, one bad decision can cause degrade to heavy oak. My advice is to do a lot of research before just firing up the kiln.

I looked at your website, and you have nice looking kilns. A commercial steam heated kiln is a very powerful tool, so when drying something fragile like heavy oak, you can do some real damage real quick. Drying heavy oak in a conventional kiln is how much of the heavy oak is dried. I use a pre-dryer, but when I dry 12/4 I opt to use only a kiln for the absolute control. Any controller can mislead you from time to time. They are subject to intermittent failure like any piece of equipment. I always back up with thermometers and/or hygrometers.

When drying heavy, I or my assistant go in and look at the lumber and samples every day, even on weekends. In time you develop a pattern for how often you need to weigh them, but I suggest walking into the kiln and looking at the lumber and samples daily. Mark existing checks going in and watch them. Know where your moisture gradient is by doing oven tests, especially before you get close to 115 degrees. When you dry heavy oak for a living you use what you have, make it work, and the end result is your report card. Myself and others I am sure have gone back into the kiln at night because you second guessed yourself and did not feel comfortable with the decision you made. It is part of drying heavy oak.

I consider myself to be a decent operator; I know of others who are better. I am not trying to scare you but I am warning you of just how big a deal it can be. You are talking more money on 8/4 and the potential for degrade goes up almost exponentially. Gene's and other books are a must to start with - I still refer to them regularly - but it goes way beyond that. It is done every day to the tune of hundreds of thousands of board feet, so welcome aboard and good luck. I just cannot overemphasize the need to use extra caution.

From Professor Gene Wengert, forum technical advisor:

Contributor K is indeed correct about being very careful. However, it is one thing to say that you need to be careful and it is another to say exactly what being careful means. For example, one might measure the moisture gradient within a piece, but what gradient is okay or too big? One can measure checks, but what increase per day is okay?

So, based on experience, we developed schedules that are to be used along with the drying rate and other factors, as stated in the book. Never would the schedules be used blindly. The drying rate gives precise values of daily moisture loss that should not be exceeded. The schedule gives RH values that cannot be drier and temperatures that cannot be hotter. The schedule suggests using cooler temperatures. Likewise, the daily inspection of samples is suggested with the idea that when checks are seen, the operator slows down the drying using the specified tools.

In the old days, kilns were slow to respond to any changes in temperature or RH and had low air flow. With today's kilns designed to dry maple, poplar and 8/4 oak, they are often running at conditions no longer expected in the schedule.

Handheld hygrometers today and in the past and many remote thermometers in the past can measure to the closest 1 degree F (and sometimes only 2 F in those old brass instruments). Controls were often 1F degree resolution and accuracy. However, today's controls often measure and control to within 0.1 F. So today's controls far exceed most portable instruments. Closer control is essential. Avoid relying on imprecise handheld instruments. A good control system can be trusted.

So, with 50 MBF of 8/4 northern red oak worth $75,000 when done drying, how much risk do we want? Usually, we want little risk, so we should, at the least, make sure we are using modern controls with 0.1 F resolution. We need to have fans that do not have too much air flow (200 fpm might be best). We need proper stacking and loading. We need proper MC samples with daily inspection. And so on. We need to use the correct kiln schedule, modifying the schedule as appropriate, following the instructions in the book. And we need to monitor the daily rate of drying - the wood's response to the kiln's conditions.

As all defects occur at high MCs, we can reduce the risk by using mild conditions initially, such as in a warehouse pre-dryer. Then when we get to the kiln, the risk of developing new quality loss is practically zero.

Finally, if we cannot live with the long drying time and the risks, but possibly low drying costs, we can use contributor D's vacuum kiln. In fact, his kiln is so easy, we could get a second job or even spend time on vacation every week. Contributor D's kiln does work... I've seen the final product.

From contributor K:

I personally invite Gene and contributor D to come stand in my shoes, keep 800,000 bf of heavy oak drying under your control at all times and then make some of your claims. .01 percent accuracy? Get real. I live in the real world, use real world equipment, work for a real world company. To say that you cannot trust a thermometer or hygrometer is absurd. What do you guys use when you calibrate, another computer? I use computers to control but I would never trust them to the point that I can walk away from them to return to a finished product from the push of a start button. You guys really do need to think about some of your claims. We live and work in the real lumber world, not a lab or university. I am surprised at some of your claims.

From Professor Gene Wengert, forum technical advisor:

There was no personal attack intended. I viewed the original question similar to a cook saying they had baked a cake, but now had to bake a double layered cake. I suggested that he follow the recipe in the book, with a few words of caution. With years of experience in baking a difficult cake, the recipe will work okay in most ovens.

From contributor K:

To say not to believe or rely on handheld devices really is bad advice, for a novice kiln operator especially. Novice in the sense that he has never dried 8/4. I have been where this guy is. He probably needs his job. He stated he had a steam kiln. He probably has modern controllers, but they are as susceptible as any to damage or failure. If he blows a charge, I don't think his boss is going to forgive him if he tells him the controller screwed up and did not catch it because he had the false impression that he should believe it over a handheld device. I am old school and I will remain so, even though I have modern equipment to use.

Contributor D, to say you can walk away after turning you vac kiln on is not accurate either. If I buy one, will you put that into a written guarantee? Gene, if the latter were true, who would need consultants?

From contributor D:

You start a vacuum kiln and then do nothing until it's time to unload. Guaranteed. I do it all of the time. I thought you were here and saw that.

From Professor Gene Wengert, forum technical advisor:

If everyone had one of Den's kiln, my business would drop indeed, but their cost of drying would increase in some cases, so conventional drying will still be used.

From contributor D:

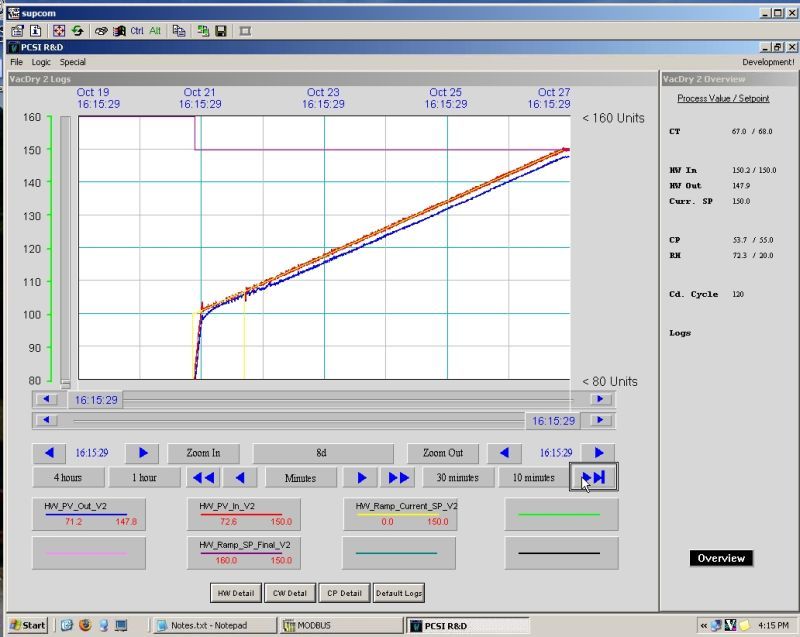

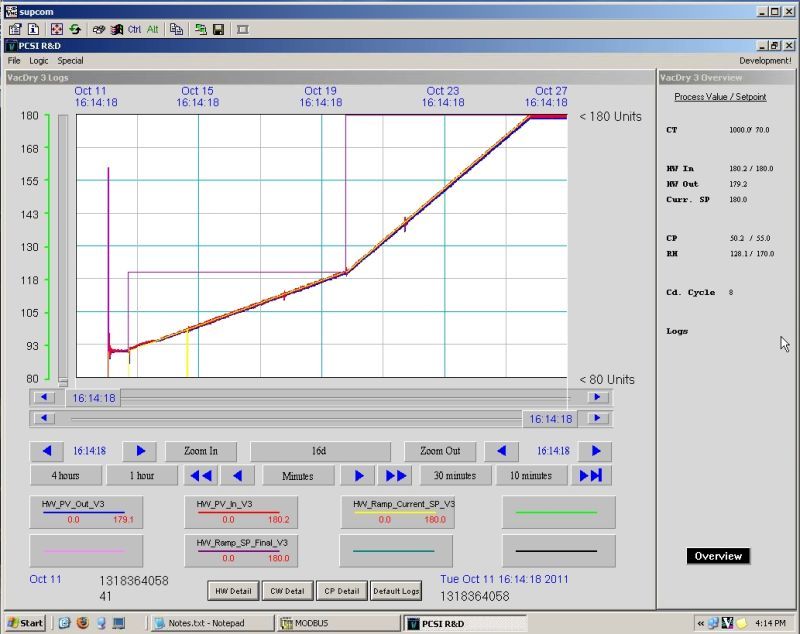

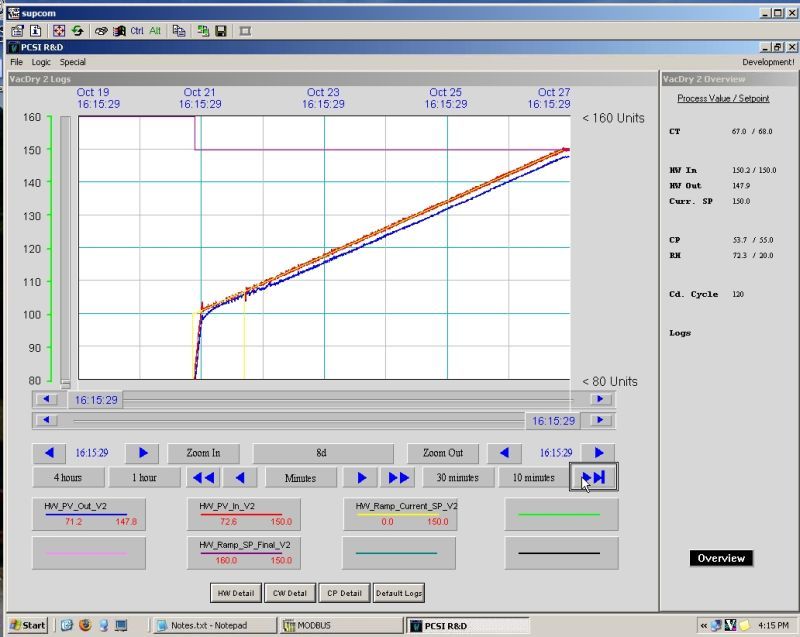

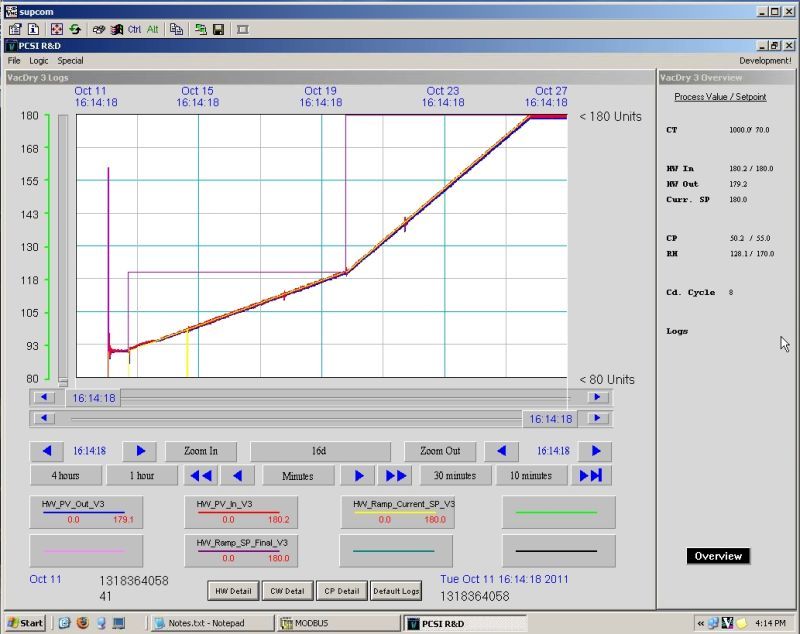

Contributor K, it bothers me that you say I am being untruthful. I took screen shots of two loads I currently have running. They show the heating ramp of hard maple baseball bats in VK2 and black walnut burls in VK3. You can see that there is no interruption or adjustment for the bat billets. You can see that I made one change in the heating rate of the burls. I was being careful because they are worth far more per board foot than your 8/4 red oak. As far as that goes, the billets are far better money also.

Click here for higher quality, full size image

Click here for higher quality, full size image

From contributor K:

Are you really disclosing all information about running a vacuum kiln? To say you do nothing for two weeks, not even monitoring anything, not visually checking the performance, not anything! When I was at your shop I noticed you measured water output of the units. Does that not compare to weighing a sample, i.e. water loss of the sample, which correlates into moisture content, which is how you derive your drying rate? When I have a computer driven controller ramp on a schedule I generate, I still have to check the performance of the equipment regularly to have peace of mind that everything is going as planned. How about your equipment - pumps, valves, etc.?

I respect the books that are out there and the authors like Gene who wrote them. I know decades of research has been poured into them. I also am impressed with your vac kilns. I think it is an interesting concept and it has its applications, but no mechanical or electrical apparatus is void of failure. That is all I meant. Regarding the thermometers, hygrometers and such, you have to start somewhere for a basis when equipment fails or appears to be inaccurate and this is where I believe in the old school methods. In my years of drying I have had one or two thermometers be off a degree or two, but when I look at three of them at the same location and they equate, I gotta think they are right and the rtd or controller is wrong. Without even opening up one of my drying manuals I know they talk of using such tools.

From contributor D:

When you were here, you may have noticed the stack lights on the controllers. Red, yellow and green. If anything goes wrong, the PLC shuts the kiln down and turns the red light on. Many days, I just glance at the kilns to make sure no red lights are on. I suppose you could call that "checking the kiln."

When I start a kiln, I set the heating ramp rate, chamber pressure, and pressure dead band. That's it. Set and forget. But I do need to add RH control if I'm drying white oak.

As far as monitoring the condensate is concerned, there is normally no monitoring until the last day or two to verify that the wood is equalized. And that is done by a glance at the computer, not checking samples.

From contributor K:

So you put all your faith in your indicator lights because they indicate that the PLC does not indicate that there is any indication that anything is wrong and everything is perfect. In the automobile world car enthusiasts make reference to similar devices used in place of true gauges. No pun intended - they call them idiot lights.

From contributor D:

I used to do a lot of checking. Pages of process logs would be filled out for each kiln charge. When the PLC software was written, the PLC took over the task of making these checks. Simple as that. By the way, Garrett wrote a lot of sophisticated software for a PLC to run your conventional kilns. You should have bought it and made your life easier. Doing things as you have for 30 years is not necessarily right. Process control systems have advanced by light years.

From Professor Gene Wengert, forum technical advisor:

One thing we learned about drying is that changing or oscillating conditions in a kiln or pre-dryer do indeed affect checking in oak. A continuous drying process where samples are not removed from their drying environment and the drying of the load is as continuous as possible (including frequent fan reversal, infrequent door opening in a pre-dryer, and so on) so that dryer conditions are essentially constant will greatly help quality. The newer control systems with proportional control, rate and reset and with very good resolution and accuracy (better than a handheld device unless the handheld costs more than $1000) dry lumber so much better than in the past. Plus the new controls use ramping instead of step changes. New control systems also have so many diagnostic features that they can tell that something is wrong before a conventional operator can detect the problem... That is, with SPC or similar, trends are diagnosed and problems indicated before the process is out of control.

Unfortunately, some drying equipment manufacturers must cut corners to be cost competitive. Some customers buy the lowest priced units rather than the best drying quality. In these cases, control systems often suffer. As one example, I convinced a client of mine in MO to change his 6/4 red oak predryer controls from conventional to Lignomat. He was, with new controls, measuring the air conditions just before the air entered the stacks rather than up near the ceiling. Measurements were very accurate with EMC values being within at least 1/2%. The first thing noted was that the temperature and EMC conditions in the predryer became very steady. Next, they noted much less degrade... Significant indeed, as a manufacturing plant is not geared to measure quality, so only big changes will be noted. He also had more sensing points. He had a large error checking routine. Finally, with the computer that was part of the system, the operator could check the conditions in the pre-dryer from any remote computer including the one at home at any time, day or night.

From contributor K:

Gene, I have the latter that you talk about. I use a computer to dry, I ramp, I time schedule when feasible. My difference with you is using a handheld device to check the accuracy of your controller no matter how good the resolution is or who made it. I can use a $20 thermometer, a $100 hygrometer, a $200 sling psychrometer or a $300 anemometer to determine the true conditions in the kiln. I and other operators do it every day. Tell me just how you go about checking conditions in a kiln if you doubt your controller.

Contributor D, I like your son's controllers. They seem very practical as does he. I just have not decided yet on a system. We are talking apples and you're talking oranges pertaining to the quantity of lumber we are required to dry. Your vac kilns are a great concept but they do not fit all applications.

From contributor C:

What is your idea of green? Was it all cut at the same time? What is your ingoing MC? How well was it manufactured? Log diameters? Amount of detectible bacteria or mineral? These are the first questions that should be answered long before anyone puffs up their chest and starts talking about their drying schedules.

Here are the three things you need to dry lumber effectively:

1) Hygrometer

2) Oven tests

3) Common sense

CONTROLLERS: Technology has pushed itself past the point where it is fully utilizable. I could care less if I can determine what the temperature is to 1/10th of a degree. In Gene's own words, his schedules were used "effectively" even with the old gas tube control/record units, so wad up your thinkin' that the fancier the control looks, the better it is. I've got a whole wall full of the latest and greatest, and I still go into the kiln every day to take readings from a $100 hygrometer. That's a number that I'll rely on.

SCHEDULES: Contributor K spent a lot of effort explaining how an operator should read and react to the lumber at hand, not what the good book says. Oven tested samples will give you a starting basis, and be your guide through the whole run. The schedules should be guides, and be considered speed limits for drying. I have never started up 8/4 oak anywhere close to the book, and would never consider it. As for working off a probe system to give you a hint of where your drying MC and rates are, good luck, and back up the firewood truck.

Keep in mind that the schedules of today were developed back when there were limitations on heating capacity, airflow capability, and venting capability. Things have changed. Also, lumber quality was much better back then. We are now drying lumber that used to be made into railroad ties, and the acceptable amount of degrade was much higher back then than it is now.

COMMON SENSE: After doing all of the above, keep detailed records and learn from every loading. Experience plus luck does not equal quality.

Contributor D, I've been down the vacuum path, and have two huge problems:

1) Stress relief

2) Consistency of moisture content.

Because you go the Easy-bake-oven route, you have no true handle on your variability. But boy, it sure was easy!

From Professor Gene Wengert, forum technical advisor:

There are four parts to an instrument reading, be it a handheld or permanent controller in drying - accuracy, resolution, repeatability and long term drift.

Can you give us the model number and manufacturer of your $100 instrument? Also, if you still have the book, can you give us any of the four items? Similarly, can you do the same for your control instrument? It would be usual to see a $100 instrument accurate to within 2 or 3 F and no better than 5% RH.

As I visit many dry kiln operations every year, I have yet to find schedules that deviate far, if any, from the book. Having worked well for 50 years, I am sure the book schedules are still good guides indeed.

From contributor C:

Most of my control units have a set-point deviation of +/- 2 degrees. If my measuring device came right from the Standards of Weights and Measures office, and I put them in my kiln, I would be like a cat chasing my tail all day. Since when have drying operations demanded such precision that we wave to short cycle our heat, spray, and vent valve actuation?

From Professor Gene Wengert, forum technical advisor:

Indeed, we are on the same page with all that you posted. When drying 8/4 red oak green from the saw in a kiln, the kiln conditions should be 3 F depression. This 3 F depression is so small and the instruments are so variable (handheld or controllers), that we do need to either have a better instrument or else watch the lumber's behavior with properly prepared and located kiln samples. It is only in a few cases where accurate knowledge is critical. In practice, drying green oak in a kiln is seldom done, so most folks do not need the close readings in everyday operations.

From contributor D:

Contributor C, you obviously don't have experience with our kilns.

From contributor C:

I do have experience with your results. When dry lumber comes into our facility, I have to do a random oven test and stress test. Company X delivered 8/4 vac dried RO recently. The oven test results were 2.1% core, and 1.8 sample average. The stress was as high as any lumber I've ever tested. Assuming that somehow the results were in error, I retested the same board, and found 10.2%. What tests do your operators do to evaluate the products after the drying process?

From Contributor D:

I don't know of any of our customers who are drying 8/4 red oak. Who could that have been?