Reprinted with permission from Custom Woodworking Business.

A step-by-step description and advice for successfully creating some of today’s most popular finishes.

By Mac Simmons

Faux finishing most likely began when selected organic materials like woods, marbles and leathers were not readily available or were too expensive to purchase. I assume that some enterprising genius decided to imitate these materials by painting them on different substrates and objects.

I also assume that it did not take long before the art of faux finishing was born: Furnituremakers built pieces and artists duplicated any material that their customers requested. Today, faux finishes are still very popular and in demand. They continue to be created in many finishing shops around the world.

In this article, I’ll explain what is involved in the faux finishing process. First, let’s review the components that make up most faux finishes. They start with a color base coat, which simulates the background color of the material that will be duplicated. In some cases, a clear coating is applied after the colored base coat has dried; this is done to seal in the background color so it is not changed or distorted in subsequent steps. However, for some faux finishes this is not done, because you may want to change the background color.

The next stage of the faux process is the application and manipulation of colored glazing. This is the key to faux finishing. It is this part of the art that makes faux finishes ageless and an appreciated treasure. Once the artwork is complete and allowed to dry, it is coated to protect and preserve the faux finish.

While the key to faux finishing is in the manipulation of the colored glaze, the background color also is integral. It is very important to match the color well. Another advantage of achieving a good background color is that once you perfect the skill of glazing and can change the color of the background, you can create all kinds of custom-colored faux finishes.

Getting Started

As with all finishing, be sure you always properly prepare your wood or other substrate. I am a strong believer in making up color samples and keeping records and formula on all my finishing materials and projects. It will help you avoid unexpected problems and re-create successful finishing jobs with ease.

To begin, look at the material you want to copy and find the same background color for the base coat. The color may be darker or lighter than the color of the glaze you will be using. The best way to achieve a good color match is by making up complete samples that have been clear coated.

For example, for a white marble faux finish, I used a white base color, seal coated it and then used a clear glaze with a little black colorant. I manipulated the glaze to give it a marble effect, then added black vein lines followed by clear coats.

For a red leather, I used a red base color, sealed it, used a black glaze to give it an antique look and then applied a clear coat. For brown leather, I would use a tan base color and a Van Dyke brown glaze.

You can see in these examples how important the base color is. But it is still only one component.

The Glazing, or 'Show Time'

Glazes can be purchased from your finishing supplier, art and craft shops or home improvement centers. You can buy colored glazes or clear glaze and add your own colorants.

One formula to make your own glazes is: 8 ounces of boiled linseed oil, 22 ounces of mineral spirits, and 1-2 ounces of an oil color of your choice.

Another formula, which dries very quickly and can be used on small work, is: 1 part of an oil color and 3 parts of mineral spirits.

You can control these glazes by adjusting the oil or the solvent. If you need more open time to work out the colored glaze, add a little more boiled linseed oil. If the glaze is taking too long to set up and dry, then increase the mineral spirits. Remember to make up samples so you know absolutely what you are getting.

The colored glaze can be manipulated with a variety of objects, including: brushes and cloths; assorted sizes and shapes of sponges; crushed papers, feathers and quills;, graining tools and combs; flat and pointed dowel rods; and any thing else you can think of to create the faux effects you want.

For a faux fruitwood panel, I have applied gesso and striated it with a comb. I then applied a French yellow ochre base color coat and sealed it. I brushed out the glaze and added distressing, followed by clear coats.

I suggest that whatever dabber you select to manipulate the glaze, you first do some testing on newspaper until you have the right pattern and color for the look you want to achieve. A word of advice: Too little color is no good, and too much color is worse! If you do make a mistake, wash the glaze off with some mineral spirits and start again.

Here is another trick that you may find helpful: After you apply the glaze and manipulate the pattern, if the glaze looks too intense, take a damp cloth with mineral spirits and lightly dab the glaze. This will soften and mute the effects.

The Final Coat

Allow the glaze to dry overnight (unless the glaze you buy gives different instructions) and then begin to apply the clear coats. Be sure your clear coats are compatible with your base color coats and the glaze (another reason why I suggest you always make up complete samples before you begin working on your projects).

I also recommend that you use water clear coatings rather than one of the amber-colored coatings that will continue yellowing over time (unless you are duplicating a restoration and want that effect).

With a little patience — some trial and error — you can soon add the art of faux finishing to your finishing repertoire.

CENTER: Brown Tanned Leather — I started with a tan base color. I clear coated it and used a Van Dyke brown glaze on a cloth to mottle out the color. I used a dampened dabber to soften the effects and lightly added some flyspecks. I then clear coated the finish.

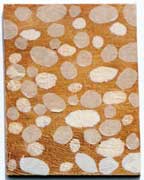

RIGHT: Burl Wood — I used the same tan base coat as for the brown leather. I clear coated it and then used the same Van Dyke brown glaze to mottle out the burl. Next I used a clean dabber with mineral spirits to soften the effect. I then took a stiff bristle brush with Van Dyke brown glaze and, with the tip of the brush, I tapped out the burl markings. I did a little flyspecking and then clear coated.

Reprinted with permission from Custom Woodworking Business.