Joinery for a Solid Teak Table

Furnituremakers advise on a tricky table construction project. January 18, 2011

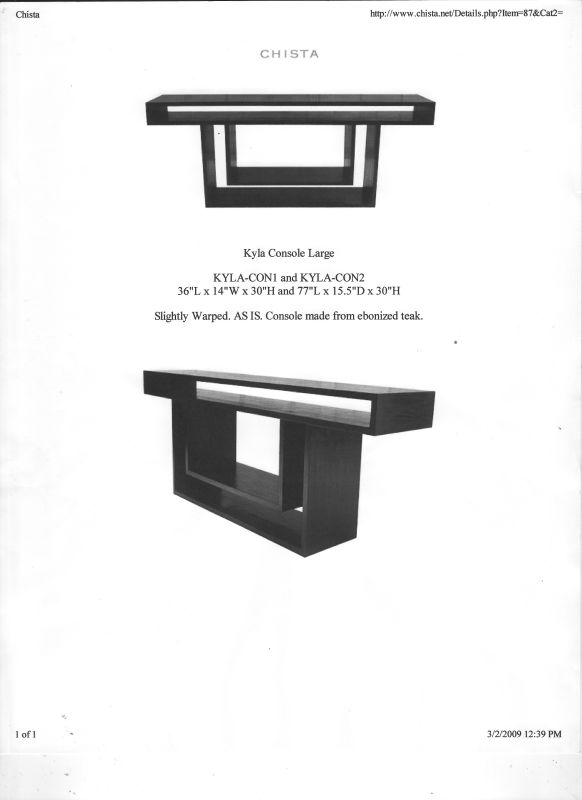

Question

I have been asked to build the table below out of solid teak. The manufacturer doesn't make it in the size the client wants. I am leery of solid wood in this case. The dimensions I have been given are 60" long 14" wide and 30" or so tall. My concern is bow/twist/cup etc. Given the design, miters seem appropriate but how to keep them tight over time makes me wonder. Should I use loose tenons on the miters and epoxy? No exposed joinery has been spec'd.

Click here for higher quality, full size image

Click here for higher quality, full size image

Forum Responses

(Furniture Making Forum)

From contributor L:

I'll bet the mfg makes this table not from solid but from ply or MDF veneer.

From the original questioner:

That was my initial reaction too. I called the manufacturer and they swore it was solid. I still don't believe it though.

From contributor S:

If you are afraid to work solid wood, decline the job. There is no reason that you should enter into a commission if you are uncomfortable working with solid wood. I doubt that panel product would span the 60" without some sag, but the one image almost looks a bit like sag. Your client certainly doesn't want to put their rock collection on that top. Solid wood will allow you to go to a thickness other than 3/4" and to will allow a positive camber to the top to counteract gravity - about 3/32" should work well, and not be noticeable.

You need an excellent source of teak, a joiner and planer and sander that are stout enough to work properly and to work teak. There are several ways to hang the verticals from the underside of the horizontals and still be blind. You need a repertoire of blind miter reinforcement from which to draw. Perhaps you can partner with someone that has the above.

A very successful artisan once told me courage is needed to succeed at one's craft. Not hubris or attitude, courage. Now, where courage leaves off and foolishness kicks in is sometimes difficult to say.

From contributor D:

The note in the picture above "slightly warped, as is" may be an indicator of how good this design is.

From the original questioner:

I agree the design is not a good idea for solid wood. Camber is a wonderful idea theoretically, but in reality, I donít know.

Contributor S - as for working solid wood, I am a professional cabinet maker and furniture maker with 16 years of experience. In that time I have seen more than my share of miters open up over time (mine and others). We are talking about a 14 1/2" wide teak board 1 1/8" thick. I will probably use splines and epoxy. The splines will have grain going same direction as boards (side to side).

Any tips would be appreciated. I do not think this is supposed to of heirloom quality and thus no blind dovetails or the like (too time consuming). As for hanging the "U" shaped piece and the legs, maybe a sliding dovetail seen only from one side.

From contributor M:

That's a slippery slope. Determining what may fail within five years, but not within one. Build it to last, or quote it with one of those impish disclaimers that the design/builder is fond of.

What size does the manufacturer make this design in? Wood joinery: keyed dovetails for the "T" joints, and box joints instead of splined miters. Perfect joints for teak are fresh from the saw or router, not burnished, wiped with acetone, tight fitting, and glued with wood glue. Epoxy has no place here.

Metal joinery: For "T" joints rout in 1/2 of a countertop bolt on the verticals that connects to a tapped steel plate keyed into the underside of the horizontals. Plug the c-top bolt cutout and "ebonize". In fact, the black stain (since I'm pretty sure that teak will not respond to ammonia) seems to give you a good deal of latitude for getting away with plugged, reinforced joints. Take advantage of low-visibility areas, and match grain with the plugs.

To counteract sag and twist in the top, build a double truss-rod out of threaded rod that's dadoed in from the bottom, then plugged. Cambering the top would probably be faster. I've done it a hundred times by accident on the jointer, so, perhaps with a little finesse in can be intentional. Or, cut a set of arched shims, tape to the bottom, and thickness plane.

Third option: swear that it's solid wood.

From the original questioner:

Box joints or dovetails and keyed dovetails for the "U"s it is. The metal joinery sounds interesting but I don't think I fully get it. Do you mean a connection like a handrail fitting (endgrain hole with face grain hole and plug) on vertical?

From contributor P:

I would just dovetail this thing together - if you have a dovetail machine it would be quite fast. With all solid it would be easy, too. Before you do anything, figure out the way you want to do it, then have a frank discussion with the client explaining your reasoning. If you are asked to do something stupid, it's your responsibility to educate the client and steer them towards a successful approach to the project.

When you do this you do two important things. One, establish your level of expertise with the client, and two, demonstrate that you have their best interests in mind. Meaning you want to build something that will last. Never agree to do something that you think won't work - better to walk away from the job.

Also, if they want ebonized, I'd also suggest substituting ash for teak - this will save a lot of money.

From contributor U:

If you have access to a construction drill that will do miters, you could easily dowel those joints. I do it often and get good results. I don't see any problem with doing it in solid wood, except I think 5/4 material would make stiffer and stronger panels. With an ebonized finish, you could substitute another species for less than half the cost.

From the original questioner:

Is a construction drill kind of like a board stretcher? If so, I know what it is. Otherwise, please enlighten me. The client really wants his teak to be used. I think I'm sold on through dovetails on the Leigh jig.

From contributor U:

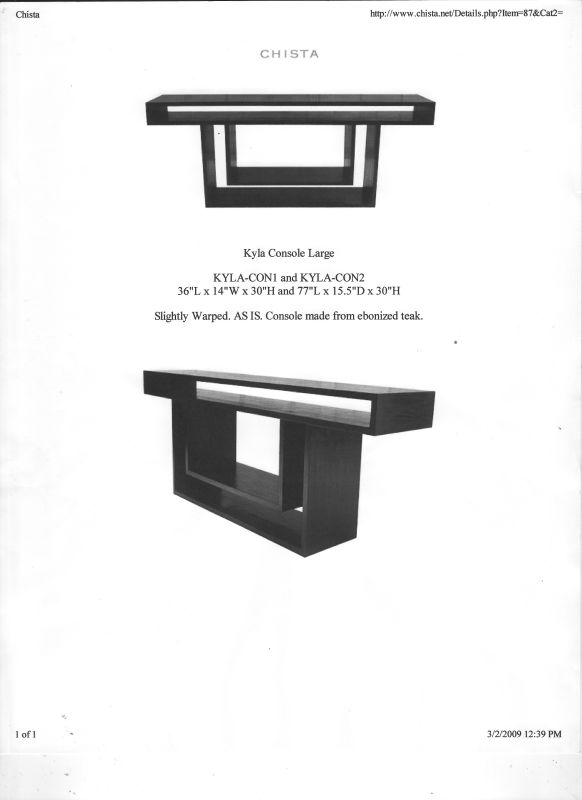

A construction drill is like a line boring machine that will bore a row of holes both horizontally and vertically and allow the use of dowels to join panels and small parts. Mine will also bore at any angle in between 0 and 90 degrees. They are typically used by cabinet makers for box construction, but they have many applications for furniture building. The piece pictured here was built with my machine. The top and sides were mitered on a sliding table saw, then bored for the dowels on the construction drill. The lower shelf and sides were also bored on the same machine. It's certainly not the only way to accomplish these joints, but it is a quick and strong way to do blind joinery.

Click here for higher quality, full size image

From contributor L:

If I might, I'd like to suggest showing the client a sample, ebonized with the dovetails. (If it was me, I'd do it in teak.) If your client's expecting a clean miter joint and gets dovetails instead, he might not be happy. Conversely, he might think the exposed joints are very cool. You never know.

From contributor Y:

Before doing any job COM (customers own material) I would put a moisture meter on every board and make no guarantees against warp or twist. Personally, I don't like the idea of a 60" span unsupported, for anything less than an inch thick.

From the original questioner:

Teak is 1 1/8" thick. I plan on letting it sit in the shop for two weeks before construction. The construction drill wins! What a fascinating tool. Just called a cabinet maker friend and he has one. I guess I need one.

From contributor U:

If your friend will let you use his drill for your piece, be sure to bore some test panels of the same thickness to make sure the set up is correct for the dowels you'll be using. I would also do a test glue up to make sure your clamping strategy is well thought out. It took myself and two assistants to maneuver all the clamps and stickers to assemble that piece in one shot.