Question

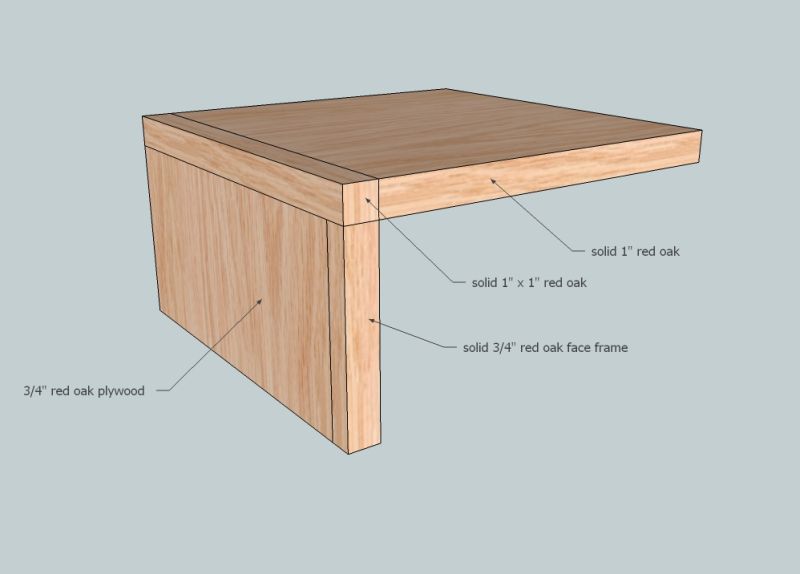

I am building a computer desk/hutch to match an existing desk design in the client's office. I am checking to see if this joint construction will work. All of the components in the picture will be glued and have biscuits for alignment. (I am not concerned about strength because there will be more support not seen in the picture.) Do you foresee a problem with the expansion/contraction of the solid 1 inch red oak? It will have 1" x 1" piece glued on the end.

Forum Responses

(Cabinetmaking Forum)

From contributor V:

Joint construction should work. A bigger question is, what is the span? The length of the top?

1. Yes, movement will be a problem.

2. I would encourage you do your homework and learn how and why wood moves. The WOODWEB Knowledge Base is a good place to start. Pay close attention to what Gene Wengert has to say.

A good book to read would be Understanding Wood: A Craftsman's Guide to Wood Technology, by R. Bruce Hoadley.

By taking your time to learn and understand wood movement, you are jumping the curb on many of your competitors. You will avoid future headaches that might involve failures, and/or callbacks. Your work will last much longer.

3. Once you have a basic understanding of wood science, I suggest you study various means of joinery, and construction. Both traditional and modern. Pay close attention to how a given method of joinery or construction allows for expansion and contraction.

4. Keep it simple. Design so that solid wood components can move together wherever possible so that you can avoid construction that is needlessly complex.

5. To further illustrate the point I made in #4, your drawing could likely be accomplished to some degree by allowing for movement would certainly pose technical challenges. A 1"x1" breadboard end, for example, is quite narrow. It may be possible if you pin the tenons with bamboo skewers. Then there is also the consideration that the joint would never remain flush with the plywood. Does this sound complicated? My advice is to find a way to simplify your design.

6. Save more advanced techniques and methods for later when you have a better understanding of what you are doing and stick with what you can guarantee. A good place to start is by reading books from credible authors. Look at what they have to say, and how they build things. Look for books from woodworking professionals who build for high end clients.

Remember the Two Rules of working wood:

1. All wood moves.

2. All woodworkers disagree as to how much, when and why.

Seriously folks, wood movement is so basic to our craft that if not understood, it will either put you under or severely inhibit your ability to prosper.

Learn the history of veneer, and you will see that once decent glues were available, the Modernist movement took to it quickly since so many of the old frame panel tricks could then be bypassed entirely - it didn't move! Whole houses and everything in them were veneered.

Frame and panel did not arise because it was attractive - it was to limit wood movement and make wood things more useful. Look at Medieval history and how plank doors evolved into frame and panel.

Ditto on the Understanding Wood - Hoadley's book. Find some good history of furniture construction and you will develop a feel for what happened and why.

In this situation I would either 1. use a veneered top rather than solid or 2. go back to the drawing board rather than attempt to find a work around to build joint as shown in the questioner's drawing while using a solid top.

Since the topic is about construction, at the design phase, a solid foundation in design begins with knowledge of wood/science, and methods. These fundamentals combined with practical experience on the shop floor represent necessary steps to raise the bar and pursue a career as a woodwork professional. Hence my recommendations.

The desk as drawn is so obviously a veneered design that to introduce solid wood will just be a cause for more work and less satisfaction for the owner. When the wood does move (and it will), those surfaces will no longer align. Will the phone ring?

Yes, you can accommodate the differential between stable wood parts and cross grain movement with slots and t&g and whatever else you want, but why? This design just cries out for veneered parts.

The Halls, as well as many others, were working in solid wood (for many reasons) and chose breadboards since it aligned with the Greene designs so well. Remember, those guys were rebelling against veneered woods and mass produced stuff. As for the Greenes, was it Henry or Charles that took to wearing the same gowns he designed for his client's wives? As their practice developed, they started to design everything, and milady's clothing was a part of it. He was a man of his own - opinions, for sure.

Frame and panel evolved as a way to limit cross grain movement (not to be confused with cross dressing) in doors and other work that needs to stay within close tolerances. It isolates the wood movement and allows the openings to receive panels that can float. While it certainly won't move as much as it wants, it will move within scientifically defined parameters that a knowledgeable woodworker will have anticipated and designed for. Basic to us, frame and panel was a big deal at the time (1600s), and is still a mystery to many today.

The Shrinkulator is a valuable 21st century adaptation of a tool that we can and should all be very familiar with, if we choose to work in solid wood, or mix solids and stable parts.

PS: I'm just starting a piece of furniture for a grandkid, all panels in hand made veneers. It would be a lot easier to do it in frame and solid panel. By the way, AWI does not allow solid wood panels in premium grade frame and panel work!