Question

I am working on a cumaru decking project. I planned to create engineered treads, stringer facings and a few decorative columns. I have done some testing and it seems the wood is case hardened.

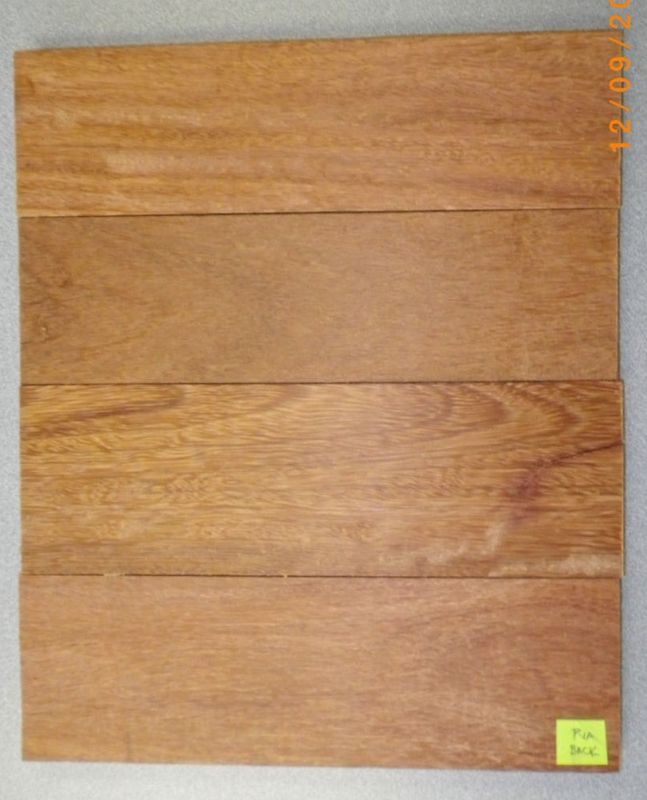

The sample veneer thickness used was a little under 1/8". The width of the veneer boards vary from 3" to 4.5". After cutting and planing the veneers, it was critical to get the material onto the treated plywood substrate within a few hours, otherwise the veneer bowed or twisted too much for vac pressing.

The moisture content of the raw lumber measures around 7% before re-sawing when the reading depth is set to 3/4" and drops to 5.9% when the depth is reduced to 1/4". The plywood measured about 5%. I measured moisture content of the completed engineered sample days after, and it has dropped to 4%+-. I am not convinced the moisture measurement of the engineered sample is correct since I only have a pinless MC device with a minimum depth of 1/4".

The problem is many of the veneers have shrunk and split while drying, so the completed assembly looks poor considering the amount of work. The width of the gaps is as much as 0.039" in the samples that used TBIII, and quite a bit less in the sample that used West 610 epoxy. The wood splits are really only noticeable near knots. I am not certain the sample made using epoxy was large enough to conclude that the rigidity of the adhesive was a factor.

1. How will they behave when installed and subjected to normal exterior weather conditions? The plan was to finish the pieces using the Messmers stain for this species.

2. Is there a reasonable way to improve the moisture problems with the wood? I am quite sure the answer to this is no.

After producing a number of custom parts (box newels, custom caps, railings) and experiencing problems throughout with warp and poor QC standards off the moulder, I am convinced the importers are not employing the same standards as the typical supplier I have worked with. The general thought at this point is to abandon the original idea, get some more material and move on.

Forum Responses

(Architectural Woodworking Forum)

From contributor J:

Sounds like you've outsmarted yourself. Veneers, plywood substrates and applied stringer facings have no business standing around outside. All of your fine woodwork will be wrecked by the elements (and sooner rather than later). You need to re-engineer your engineering (and cumaru "ipe" ain't teak).

Start with solid teak and end with solid teak (forget your moisture meter for now). Glue and screw everything, allow for movement and life - caulk open seams. Insert stainless all-thread completely through furniture or other fixtures which absolutely must stick together. Finish everything with copious quantities of oil, varnish or cetol and instruct the new owner to do likewise as often as humanly possible.

Compared with teak, ipe is icky and no herd of hairy gorillas or epoxy will ever keep it stuck together under the summer sun. What goes up (in ipe) must come down, and you'll be the guy taking it down. Been there, done that.

I think it may be fine as big and thick decking and treads, but I would never try to glue 2 pieces and expect them to stay together outside.

I had a customer specify it - because it is "like teak" (it is not - far from it). I tried to talk him out of it - if you want teak, use teak. We both regretted it by the time we had gone through and repaired open cracks and glue joints for the fourth or fifth time in 3 years.

If you do use teak, use resorcinol glue. I used to make doors for Chris Craft restorations and this was the specified glue. It worked very well - better than epoxy. It likes to be clamped and so does the teak.

Teak would be wonderful, but I have processed almost 500bdft making railings and the like, so the cost would not have been feasible for this couple. The engineered concept was for only some miscellaneous parts that will use a larger volume of wood.

I was surprised by this problem. I have not experienced this with tigerwood or jatoba. I did mockup tests of engineered tigerwood items where the wear layer was saturated and no problems resulted.

Does the resorcinol work in a vac press or do you use something that generates a larger clamping pressure? I like the epoxy since it does not require a large clamp pressure and is a great gap filler.

I did conventional interior millwork and the glue joints were the problem, but nothing stayed truly flat - even 1-1/8" thick stair treads moved, with all that crazy interlocked grain.

I was hoping to see your final result and see it do well so I could add it to my collection of amazing facts about wood. You have obviously spent some time and effort, so I trust you have it all thought out. If I recall, your climate is coastal Mexico, so that will be a test.

I did test the glue joints, and the TBIII glueups failed in very short order after applying water to the surface. The samples glued with epoxy did not show any signs of glue failure, but I know this is not a conclusive test since it was only one cycle.

After installing the deck boards, we were surprised how much the surface cupped and cracked after a few days of heat in our dry climate. It was actually to the point that we sanded the deck before finishing. There are some areas we went back and screwed (plugged) the deck boards since the hidden fasteners were not holding sufficiently. Maybe this will not be a problem for you given your climate.

My general conclusion after this project is that this wood should be left in Brazil where it is happy. I too would be very leery about using this for what you are doing.