Preventing Cupping in a Wide Board

Woodworkers discuss the "rip and flip" method, relief cuts, and similar methods of reducing wood movement. November 19, 2005

Question

I am making door jambs from Jatoba, approximately 7" in width. I would like to saw them into two pieces behind the door stop and glue them back together to prevent cupping. Does anyone have any past experience with this?

Forum Responses

(Architectural Woodworking Forum)

From contributor A:

I haven't worked with Jatoba so I don't know if it's better or worse about cupping. However, your idea of 2 pieces will help reduce cupping, no matter what species. I think I would join the two pieces back together with a tongue and groove or maybe a shiplap joint. You could also provide relief cuts on the back side of the jambs. Several saw kerfs plus or minus 1/8" deep would work. Also, don't forget to nail the stop to only one of the two pieces so that if the jamb material moves in different directions, it won't split the stop.

From contributor B:

Breaking the continuity of the grain is a good method of large cup prevention. You will effectively get two small cups instead of one large one if you split the board into two. A jointed edge long grain glue-up of the two pieces will be stronger at the joint than solid wood. I see no reason to use tongue and groove or anything else. I believe the two joined pieces of wood will move as one, like a glued up raised panel in a door.

From contributor A:

I should have been clearer in referring to the tongue and groove or shiplap joint. I would not glue them together, rather let the joint serve as a slip joint. Although this won't necessarily help with cupping, it will maintain the same plane for the two surfaces while allowing for cross grain movement that will occur with a 7" wide board.

From contributor C:

Jatoba is a pretty stable wood in my experience. The standard way of stabilizing any solid stock is to rip and flip the boards so that the board is balanced in both directions. This will force the glued up piece to be straight.

From contributor B:

That is a method to deal with bow, not cup.

From contributor D:

The rip and flip method actually aids both the bow and cup!

From contributor E:

Cupping is relative to two factors - change in MC, and the arc of the annual rings from the end-grain. The smaller the radius of the arc, the greater the cupping will be relative to change in MC. The closer to the heart, the more the board will cup. Wide, flat-cut lumber with annual rings more parallel to the face is less prone to cupping. Quarter-sawn lumber is not prone to cup. If you are not assessing these factors, you may be wasting your time adding unnecessary labor.

From contributor F:

Why is it a given that a 7" (assumed 3/4") piece of wood is going to cup? If this is true, aren't we all doomed as woodworkers? How can anything ever get built? The fact is, if the wood is properly kiln dried, it won't cup unless there is a significant shift in the RH and therefore the MC of the wood. And then, if the moisture change is significant, the cup will occur depending upon which side of the board is gaining or losing moisture and somewhat relative to the extent of finish on either side of the board. The idea of the annual rings determining which way it will cup is a myth and I challenge anyone to demonstrate it as true any way other than by anecdote.

With all due respect to the experts, this concept of ripping at 3 maximum width and flipping and then gluing for width doesn’t cut it in the real world. Try explaining that bit of mythology to the people that want those 18" wide slabs of Walnut turned into tables, or in Nakashima's shop.

This chunk of Jatoba door jamb is likely to move only as a result of bad transport and/or storage conditions rather than in service. You should insure that the jobsite conditions are favorable for delivery of the wood, and the job super is awake and aware of the problems caused if the site is not controlled properly. Check with hardwood flooring people as to correct conditions.

You can two-piece it behind the stop if it makes you feel better, but look up Jatoba in the Shrinkulator and plug in some realistic values. It's not going to go anywhere.

Sorry to be so skeptical on this, but it is disturbing to see a group of otherwise intelligent, capable woodworkers go dancing down the crooked path following a mad piper without anyone injecting a bit of common sense.

From contributor C:

I said in my experience Jatoba is stable, and that the standard way of handling this is rip and flip. It is probably not necessary for jambs. For larger glue ups rip flip is worth the time in some situations and is a known and accepted practice. But the question was how to prevent cupping.

From contributor F:

The straight answer to preventing cupping is to use properly dried lumber in normally accepted ways, and relax. The rip and flip concept is busy work, even though it is an accepted practice. The cupping I have seen over the years was always due to over wet or over dry wood that was exposed to changes in RHumidity, and more so on one side than the other. I have done exterior jamb and trim for 30 years and you do not see good wood that is properly dried, used and installed, cupping in service.

From contributor G:

To contributor E: I think you may have made a typo. Quarter-sawn is not prone to cupping and has grain perpendicular to the face, as you said. It shrinks and swells in thickness. Flat sawn (towards the perimeter of the saw log) has grain more parallel to the face and is indeed prone to cup with different moisture contents on opposite sides.

I agree with contributor F that 7" isn't wide enough to worry about, especially for a door jamb. I would be more worried about the jamb loosening up without casings attached to both edges than cupping. Running the backs of the jambs over the table saw a few times will eliminate any possible cupping, and if this is prone to splitting out you could use a router with a core box bit.

From contributor C:

I became aware of this practice by reading a Jerry Metz column. He repeated the importance of checking MC and for tops ripping and flipping. He has glued up more solid stock then you and I ever will. The point is that it is a good practice, in addition to checking MC. I occasionally have trouble with MC but also on occasion the rip flip has been an issue.

From contributor B:

It is recommended in many books I have read to break the grain continuity on wide boards (12"wide and up) and glue them back together, but nothing was said about flipping. I get rock Maple occasionally that is case hardened and will not stay uncupped even at 10" wide.

From contributor H:

I have a similar situation. I have to make 7/8" x 12" x 48" cherry stair treads for a house in a coastal area that is very humid in the summertime. Should I rip and flip? I can't back relief the treads because they will be seen from the underside. What does flip mean? Turn over, or rotate end for end? Or both?

From contributor C:

I don't want to go against the grain any more.

From contributor G:

If the treads will be seen from the bottom, the moisture content will be uniform throughout the tread and it should not cup. I imagine that they will be dadoed into the stringers as well which will also prevent cupping.

From contributor B:

I agree that if the moisture is same for both faces it will not cup, unless it is casehardened. I also agree that if a board is fastened down well, cupping becomes a non issue. I also agree that until you get up around 12" across the grain it is not a major concern.

The flip part of rip and flip means turning one of the two halves end for end. I bring this subject up to say that the flip part is only necessary in my estimation if the board is bowed along its face.

In that case, when you flip, the two opposing bows will straighten the board. I flatten my stock so if I had a wide board that I felt would cup, I would part it in two to break the grains continuity and then glue it back up the way it grew so it would look like a whole board.

From contributor D:

It has always been known that reversing the direction of the growth rings, as in rip and flip, is the only way to minimize the severity of cupping in a board if it is going to cup. Wood properly dried should stay flat if kept in a reasonably controlled environment. I learned the hard way 25 years ago in some of my first self taught projects that simply ripping and gluing back together the way it came apart does nothing to minimize cupping because each ripping is still going to cup within its own width, and if its inherent direction to cupping doesn't change then nothing is gained.

It is not a myth that wood has a tendency to cup to the outside of the growth rings. That is a known inherent characteristic of wood. I do agree that wood can cup to either direction if enough moisture gain or loss exists in a greater amount on one side than on the other. Even quarter-sawn lumber can cup under extreme change, but in the normal humidity conditions and the kiln drying quality we have come to expect, this rarely happens.

From contributor C:

To contributor H: How much is it going to cost you if the boards do cup or bow, and you have to replace them? These stairs are going to be at least 30" wide

From contributor H:

The treads are 7/8" thick x 12" wide x 48" long. They will be seen on the ends, but not from the bottom. MC differential top face to bottom face is a design factor. Regarding your point, I will not take a chance. The customer is adamant that we plan for coastal humid conditions.

From contributor G:

To contributor D: The statement that wood tends to cup toward the outer rings is generally true. It was even more generally true years ago than today. That's because that information was handed down from sawyers. After a log was sawed the boards would cup, as you say. After the boards were machined they would continue to cup, but to a lesser degree. This is because they were continuing to lose moisture, even after they were machined.

Given equal moisture content throughout the entire board, the direction a board cups depends on which way its moisture content goes after being flattened. Further drying will cause it to cup towards the outer rings. Increased MC will cause it to cup away from the outer rings.

Contributor F obviously uses good material and keeps the MC from fluctuating while work is in progress. Therefore, the direction of what little cupping might occur after his products are delivered depends on the conditions in his customer’s homes. And I'm sure that his joinery techniques eliminate that potential problem anyhow.

In general, cupping today is primarily an issue with wide plank flooring. And that, again, is due to unequal moisture content in the same board at the same time. I've bought numerous diced cherry logs from Hearne Hardwoods and prior to that, from Groff and Hearne Hardwoods. The narrowest boards from these logs were sometimes over 20" wide. I often ripped them in half then glued them back the same way. This was not because I was worried about cupping, but because my thickness plane would only handle 24" widths. The issue for me was always width changes, not cupping. But you are right - rip and flip will make two little waves instead of one big gentle swell.

From contributor G:

To contributor B: Your method of ripping and not flipping will also aid in reducing cupping provided the ripping is done in the rough, then the machining, and then the gluing. It will not be to the degree that you get with the flip.

From contributor B:

To contributor D: If your goal is to have it look as close to a whole board as possible then gluing it back together the way it came will give you two individual cups and will be less of a problem and less pronounced than one large one across the entire width, so something is gained.

It is true that reversing the growth rings could give you zero cup, but it doesn't look as nice or go through the planer as well. It all depends on your particular wood working situation so I think we are both correct.

From contributor E:

The question here is the ratio between tangential, and radial movement. The average is T 2 ~ R 1.

As I stated earlier, when you view the arc of the rings from the end of the board, the greater effect will be when the board moves relative to change in MC in either direction.

If I glued up stair treads, starting with wide flat cut boards that have a tight arc to the rings in the middle, I would rip them down the middle, and flip the heart out to the edges, while gluing the rift-cut portions in the middle. I usually try to discard any juvenile wood that is too near the heart if I am making wide panels.

From contributor I:

To contributor H: You better make sure about the thickness of your treads. 7/8" is pretty flimsy. Most use 1-1/16" according to whatever the local code may be.

From contributor J:

I just got 3/4" thick Ipe treads approved. Jatoba would probably span at 7/8” what oak would do at 1-1/16".

From contributor K:

My recommendation for the jamb is joint, plane and relief cut the back side.

The tread should be ripped to 3-4" wide pieces and oppose grain.

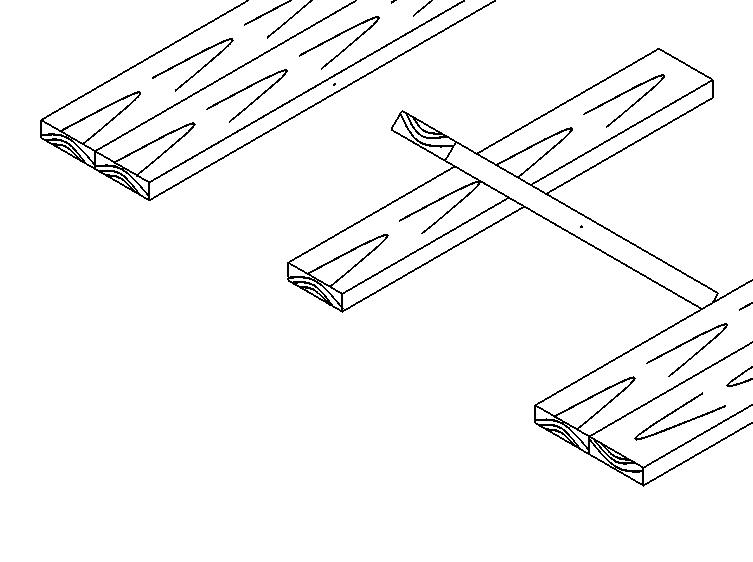

From contributor L:

If the job requires planning for moisture in coastal conditions, why not use quarter-sawn material? It is naturally more stable than flat-sawn. Its narrower width will force you to glue up the treads, and since the grain will be rather straight, you should be able to make the treads appear to be single pieces of wood.

The attached photo shows quarter-sawn mahogany trusses over an indoor pool (humid) which is located about 500 feet from Long Island Sound, a coastal location. We installed the trusses two years ago. I was at that house a month ago and they looked as good as they did right after installation.

Click here for full size image