Question

I'm new to the business and am looking for better ways of doing things. I'm currently building my cabinets with the backs flush to the gables. Many cabinets I've seen have the gables extending past the back of the cabinet. Which is better and why? Is it a matter of material cost or is it an installation consideration?

Forum Responses

I may be odd, but I use 1/2" for backs, planted on and screwed. Finished ends cover the exposed edge. Costs more, but is a lot quicker for me than to dado the back for recessed or plant on a 1/4" back. Both require more time by cutting/installing a nailer. Don't like nailers, but that's just me. The difference in cost on a typical kitchen here is roughly $50-$60. But time saved is worth $100 to me. Also, makes screwing to the wall a bit easier. But I know many shops who use 1/4 very successfully, too.

I’ve been applying a 1/4" back flush to the carcasses for 12 years and so far no problems. Square boxes are more a function of square parts and square edges where these parts meet, then whether or not the back sits in a rebate.

If you insure that your parts are square and your back is square, your box will be square. Well, that’s how it has worked for me, anyway.

I'm building my boxes with 3/4" backs planted on. This gives me a perfectly square cabinet. The larger manufacturers around town slide the back into a groove running along the sides, bottom and top of the cabinet. This leaves an overhang of about 3/4" where the cleats are then placed. The reason for my asking the question was that I'm having a hard time hanging the cabinets on walls that are neither plum or flat. The back of my cabinets follow the contour of the wall which has a mind of its own. I began to think that the reason for the "slotted back" was to allow scribing on the sides which protrude. Any suggestions?

I've used French cleat - less likely to fall, but the bevel makes the cabinets ride up if the wall is bowed, and it seems all walls are bowed!

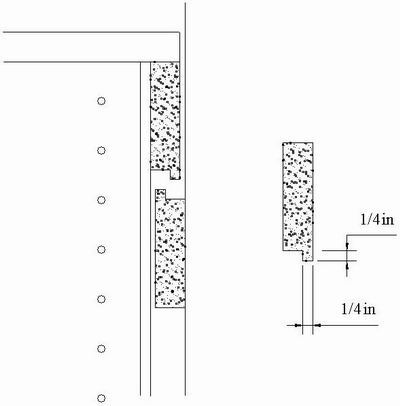

Now we use tongued cleat with a 1/4" tongue on 3/4 thick cleats. That gives 1/4" of play for the cabinet to ride away from the wall, compensating for all but the most horrendous bows in the walls.

With hanging cleat, you do not need to screw the box hard to the wall which usually will rack the cabinet.

Very easy to cut a job. Since the backs are the same widths as the tops and bottoms, they can be cut at the same time. No edgebanded nailing strip to deal with. No fooling around with dados either.

Virtually the same interior storage as 1/4” backs, since the dado must be set in from the backs at least 3/8”.

Superior to using 1/4” when it comes to keeping the box square (although either way is probably good enough).

Installation screws can be placed anywhere. This is valuable to me because about half of the upper cabinets in one of my typical jobs have glass doors. To hide the screws, we place them in the same plane as the muntins (where the shelves will hide them).

We make our boxes so the entire back is flush. Extra deep end panels take care of wall variations.

Granted, the cost is slightly higher, but not by much. The added weight isn’t much of an issue either (so long as we’re talking plywood, not melamine).

The only place I've ever seen the term "gable" used to mean "cabinet end panel" is from Danny Proulx in his articles and columns. Interestingly I ran into the term "bulkhead" in this same usage early in my career and it stuck. We still refer to them that way. Anybody ever heard this term?

I always made the carcass out of 3/4" material only. I would then attach the face frame with biscuit joinery, and let dry a minimum of 12 hours. I then would remove all clamps attaching the face frame, most of the time 16 minimum, depending on their size. I always used 1/4" material for my backs, but you must also glue them for strength. Otherwise, depending on the wall condition, they can pull the backs right off, and all your hard work will be for nothing. The backs also assure a square cabinet, providing your saw is square, and you should check diagonally also. I always used 3/4" cleats to hang them from. For kitchen cabinets, I've never required a thicker back, but for a different type cabinet, you might need to make a change. I can't imagine using a back thicker than 3/8", but when I was doing this type of work, 3/8 wasn't available, at least not in birch, walnut, or oak. Therefore I would use, I believe, 5.4mm luan mahogany, but depending on your geographical location, that might not be a stock item. If you're working alone, a French cleat is a big help also.

It may be overkill, but there are so many advantages, from ordering to assembly and installation, along with the marketing benefits (perception goes a long way), it just makes sense.

The concept is this:

1. Install a hanging bracket in the top right and left corners of the box. I do the boring for this with a simple jig when the cabinet sides are flat on the bench.

2. Install the hanging rail at desired height. 1 5/8” from top of cabinet works best for me. Fasten to studs, and use toggle bolts between studs. I cut the hanging rails in the shop and mark cabinet locations on them (a story pole for the installation).

3. Once rails are secure, lift the boxes onto them, slide into position and level using the adjusting screws on the hanger brackets. Once I have the cabinets close, I fasten them together, double check everything, then tighten the whole run of cabinets to the wall.

I realize that this adds another setup to your cabinets. One more thing to do. Why? How many times have you put a screw into a cabinet that missed the stud, or had a cabinet that ended up with only one screw supporting its weight? How many times have you sent two guys to the install so one can hold the cabinet while the other is screwing? Or how about those times that the cabinets move just a bit as you tighten them up, and you have to try and adjust, but don’t want that extra screw showing inside?

This is something that can take place in the shop with simple jigs. Once on site, I can hang an entire run of uppers by myself. I can get every cabinet dead level, plumb and square with a screwdriver once they are on the wall. Cabinets can be taken down easily to scribe, then put back in place and adjusted to perfection – taken back off and put up again – no changes to adjustments. And it’s strong! I’m over 230 lbs, and I hang off of every run as a final check.

With that in mind, we use 1/4” cabinet backs and dado into the side to leave 1/2” of space behind the back to the wall. This accommodates the hanging system. We rip our tops 3/4” smaller that the bottoms and sides (11 7/8” sides and bottoms, 11 1/8” tops). This allows for inserting the cabinet back into the finished box, and also allows for the hanging rail to be continuous along the cabinet run.

Comment from contributor L:

I've read a lot in this discussion about recessing the back panel into dadoed sides to provide a lip to scribe against an uneven wall. This seems like a lot of work compared to planting the back onto the sides, and then gluing a 3/4" square pine strip vertically along each side of the back for scribing, at least for cabinets not on the end. Since it has very little stress on it, you don't even have to clamp the strip. Gluing it means you don't run the risk of hitting a nail with your scribing saw. I cover exposed end panels with 1/4" plywood anyway.