Solid Wood Door Construction Methods

Other Versions

Spanish

French

A long discussion of various ways to construct heavy wood architectural doors. April 4, 2011

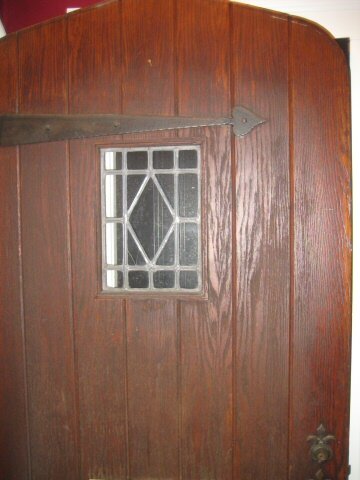

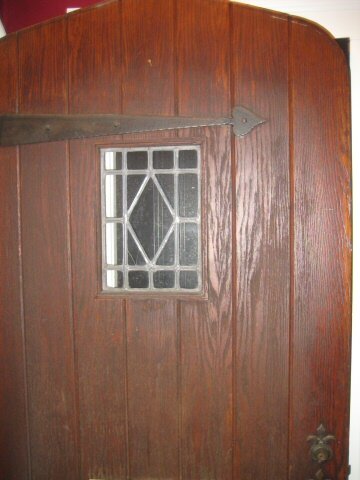

Question

I had an inquiry to build the type of door below. How is this constructed? Is it a glued tongue and groove? Or is it a floating tongue and groove with loose tenon in it, glued at the outer stiles and the inner styles float. Or is there another construction method to construct this type of a door?

Click here for higher quality, full size image

"Photo by Leo R Graywacz, Jr."

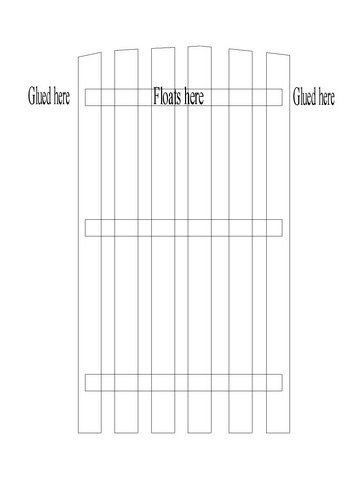

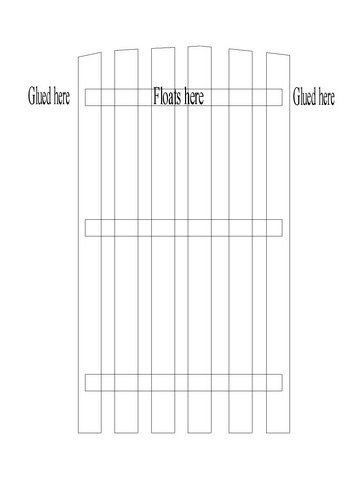

This is what I mean by the floating Mortise and tenon. Glued on the outside stiles and floats on the inside stiles. Exploded view shown.

Click here for higher quality, full size image

"Photo by Leo R Graywacz, Jr."

Forum Responses

(Architectural Woodworking Forum)

From contributor O:

We build these doors, we call them plank doors, with what we call a ladder frame. It is a mortise and tenon stile and rail affair that is about 3/4" thick. This is the center core of the door. Then it is clad on both sides with tongue and groove planks. Windows and other things can be accommodated easily.

The ladder core gives the door stability and eliminates/reduces wood movement in the same fashion as a conventional frame and panel door. The ladder core also gives rigidity against sagging with generously sized tenons and several horizontal rails. Sagging is what many board doors do - hence the z or x braces to triangulate the load.

When attaching the planks, leave about 1/16" space for expansion since most wood will grow a bit once it leaves the shop. Each plank moves in its own little place, without joining the others in warping, expanding or compromising the entire door. We use 3/4" planks and insulate the voids in the ladder core for 2-1/4" exterior doors, and go to 1/2" ship lap for interior doors at 1-3/4"

Click here for higher quality, full size image

From contributor D:

I will attest Contributor O's method works, but don't use it anymore. Our plank doors are basically one big engineered plank, consisting of perhaps three hundred small pieces covered in 1/8" thick veneers. A 3" deep breadboard is glued in across the bottom. V-grooves on the exterior side are stopped 1/2" away from the top edge for a better weather-tight fit.

After several hundred of these I can say they all stayed flat. We only built a few with shiplapped plank over frames and had a few complaints. Basically trying to educate a customer about wood movement wasn't being bought. They said all the planks felt like they were coming loose when they rapped on the door, which sounded hollow as well. They wanted something solid and heavy and that's what we ended up giving them.

They're basically solid core doors comprised of small sticks glued up instead of particles. The worst thing that has happened was a few years ago some 42" wide 2 1/4" thick slabs were sitting at a jobsite for several months in the weather with no finish on them, and they grew in width 1/4". They were fixed onsite by the customer with a hand held power door planer.

That said, I think your idea looks sound. Only problem I can see may be setting the speakeasy glass into a small sash which has to float between the planks. An overlapping trim around this will hide expansion gaps, but may not be weather-tight due to v-grooves.

From contributor O:

Contributor D's method is certainly viable, and he can get there in good time. Our method resulted from research over 30 years ago into successful door construction in doors from 1900 to the '40's.

We overcome the weatherstrip problem with a spring bronze seal on the jambs and forego the compressible foam. That type is considered a premium in our market. The builder that ordered the door in the photo insisted on the foam for 'extra' protection. With 3/4" thick planks on either side of the door and foam interior, the doors feel and sound very solid. They are pressed in a vacuum press in one pressing. Some refer to our plank doors as castle doors and rap their knuckles on the face to emphasize the solidity that they were looking for.

Either construction solution yields a stable door. We have found that people like to hear words like 'solid' wood and planks. While our methods could also be called 'engineered' we have found some folks are leery of that word, in favor of old style methods. Different strokes for different strokes, but one is not inherently better than the other.

From contributor K:

Contributor D, I am curious about your engineered core. Are you using a solid wood core made up of many small fingerjointed pieces of wood, or some other material? At our shop we sometimes use slices of fingerjointed pine door core sheets as a base for veneered parts of stile and rail doors, but not as a full width core for a veneered plank door. We have built a number of exterior doors with an outer skin of 1/8" to 1/4" veneers over a substrate of Extira MDF and an interior solid wood frame filled with insulating foam that have held up in exposed settings for five plus years. In fact I built one last weekend for the back door of my own home shop, and I am reasonably confident it will outlast me (though that may not be saying much at this point). I chose that construction based on surplus materials at hand, random leftovers of cypress veneer from a previous project. That said, the front door will be a 2 1/4" Spanish cedar plank door with ladder frame core as per Contributor O's description, as I feel that method has a longer track record and I like working with solid wood. I built a similar door for my son's cabin two years ago and it has fared well so far.

From contributor D:

Shiplapped plank over frame type construction is used by many folks with success, but like I said we don't do it that way anymore unless someone insists on an exact replica. A guy on here a couple months ago built one that was warping enough to bend a steel frame. Plenty of them out there are just fine like yours. I take issue with speakeasy designs though, and have seen problems with their use in those floating shiplapped planks. The perimeter around them develops expansion gaps and compromises weathertight integrity. The unsightly gaps usually get caulked and covered with an overlapping trim around it. Rain over the years that hits the door runs down the surface and collects in the small pockets where the v-groove runs down to the trim around the top edge of the speakeasy. It sits there and eventually wreaks havoc on the trim which warps, rots, and falls off someday when the door is slammed. Sometimes the speakeasy falls out too. Ours are set in flush which allows rain to run off. A large part of our customer base is contractors remodeling old homes, and I've been fortunate to be able to examine and dismantle many old doors before replicating them. Points of failure sometimes dictate a design change, and that one has been a recurring one over the years.

We build up our cores in house, using an RF press and one of the best adhesives on the market. The commercially available pine fingerjoint I feel is a poor substitute. The outer layers of the core are the same material as the veneers, so you don't see a color change in the v-groove. The only time we use thicker veneers is in distressed or antiqued orders where gouging would penetrate a thinner layer.

Time will tell if engineered slabs work I guess. The oldest we have are about eight years old and looking good. I have no idea when solid core doors hit the market, but I've seen many I know are at least twenty years old, including one on the back door of my garage.

From contributor K:

I would like to know more about the construction of your door cores if you are willing. It seems you are building a multilayer panel; do you have crossgrain plies making it the equivalent of plywood/? Do you joint short pieces for length within the layers and edge glue them for width? What is the function of the breadboard ends? How thick of a face veneer do you use?

From contributor D:

Our cores are made up basically from rip scrap throughout the shop. We trained the cleanup guy to run a straightline rip saw, and he rips up lineal falloff from tablesaws to 1/2" wide. He carts all the strips to the RF press, where it's edge glued with Spectrum RB-201 into 10' x 3' sheets, planed flat, and stored. Cores of various sizes are built up from this stock, which is extremely stable, mostly Sapele mixed with other hardwoods.

Core buildup is unidirectional throughout, with no alternation of grain. All doors use engineered core where it can be used, including rails and sidelight parts. Radius parts or carved components of course are solid. Pine fingerjoint we bought years ago had maybe one in ten stile cores warped when we recieved them, and even with a return policy that trash didn't look very attractive for use in our doors.

The breadboards are for countering delamination, which always happens on the ends of glueups rather than in the middle, and also for reducing exposed endgrain along the bottom, which is where most moisture gets wicked up on doors (except for outswing units, where the top is usually the first to develop problems). None of our cores are ever exposed in a finished door - they get covered by one inch edgebands, caps and the face veneer. Veneers are mostly 1/8" unless it's an antiqued or distressed order.

From contributor O:

Contributor D - as I read it, you make a core of solid wood that is 1-1/2" thick x 36 x 84 - for example, and then apply face veneers of 1/8" to each side. You let in some horizontal grain at the top and bottom to control delamination. How do you control or limit cross grain expansion?

From contributor D:

Breadboard ends can't control the expansion. These kinds of doors expand and contract more than stile and rail doors, and we hang them in frames where inside jamb measures fully a quarter inch more than the door. Breadboards are glued in but when viewed from the edges they'll be recessed about a 1/16" after a winter (more for wider and thicker slabs). The glue seems to hold, as the edgeband grain swells around it, slightly bulbous instead of squared off. They seem to shrink right back in dry summer heat. I've read on here how wood only moves with humidity and it's the gospel, but put a sealed 1/2" flat sawn board under a heat gun and watch it curl up like a potato chip (just more stuff I think about that may or may not matter). Anyway, they fare better with than without the breadboard ends, mainly I think because of poor sealing by our customers. You know, an even coat on all six sides isn't so even when end grain absorption is greater. The big manufacturers have breadboards in their solid core doors, but they aren't solid wood. Looks like a composite of wood and rubber wastes.

From contributor K:

That is an interesting construction. If you have built several hundred of these doors and all of them have stayed flat and none has grown more than 1/4" in width I applaud you. I am a little skeptical, but then I am a curmudgeon. I take your point about inserted windows. I basically approach them as if I were installing them into a wall. By the way, what does engineered mean?

From contributor D:

We're proud of our doors here but I assure you we've had our fair share of repairs and replacements. This particular style has so far a better track record than any we build- well, except maybe Douglas fir doors.

By engineered I mean small pieces. A 1/8" inch thick veneer is limp. A 2" thick board is stiff. Everything moves though, and a cupped veneer you can bend with your hands. You need a vise to say, flatten a cup in a board, where it will likely crack before taking the shape. Movement in wood is also volumetric. A percentage of the total volume shrinks and swells. Bigger the volume, the more it moves. Small pieces move very little. The glue we use is strong and surpasses every waterproof test used by the industry, so each little piece in the core is very insulated from each other and thus from moisture.