Stickley Design

Other Versions

Spanish

French

A question about Stickley style provokes answers starting with a discussion about rift-sawn and quartersawn oak, and ending with a wide-ranging ramble (or was that rumble?) about Gustav Stickley, the Arts and Crafts movement, history, and the philosophy of work and play. Some pictures of cabinets here, too. July 5, 2006

Question

I am going to bid on a kitchen job that the client wants to be in the Stickley style. I was wondering if any of you could point me to a site that might have a kitchen in that design style. Or better yet, post some of your own Stickley style kitchens.

Forum Responses

(Cabinetmaking Forum)

From contributor A:

We do a fair amount of this kind of work. Our typical door frames are made out of rift sawn white oak. The inset panels are usually custom pressed veneer, either rift or quartersawn. Something to watch for in the rift lumber is that the boards are fairly narrow and can sometimes run to sap pretty quickly. It is very seldom that the board is wide enough to present good rift grain and still be able to get two stiles out of one plank. Figure about 40% fall down minimum if your customer is just modestly interested in grain selection.

The other thing to watch for is quarter-flecks. These are really desirable boards as quartersawn but can sometimes confuse your customer if they are expecting calmer, straighter grains. It's hard to get rift lumber without some quarter fleck and you should make sure the customer knows what to expect. We've covered this grain expectation chat many times and if the customer seems unrealistic in what they think a tree should look like, we propose to sell them labor to build the kitchen and act as their agent when buying the boards. We just keep buying more lumber till they tell us it hurts. Most customers are pretty reasonable if you do a good job of managing their expectations.

From contributor B:

With the Stickley design, your customer may want more quartersawn than rift. But I've found that there is such a thing as to much fleck. If you only use boards with the wildest fleck, the end result will be a crazy psychedelic looking set of cabinets. Right now we're doing an office out of quartersawn red oak. We're mainly putting the heavy fleck wood into things like door panels and drawer fronts etc., and going with the grain wood with the most rift for door and cabinet frames etc. It looks plenty quartersawn but doesn't make you dizzy when you look at it.

From the original questioner:

Is the Stickley style just that you use quartersawn Oak? Or are there some design factors involved also? Iím trying not to look uninformed when I show up at the clientís home. I really have no idea about the Stickley style so treat me as a dummy in that respect. It should be easy enough to duplicate once I know what the look should be. Pictures or links would be nice.

From contributor C:

Stickley usually refers to Gustav Stickley. He had a cabinet shop in Michigan about 100 years ago -Arts and Crafts mission style furniture, etc. He was the guy that brought that style out and made it real popular. I believe he is credited with making it happen. Sounds like your clients did their homework so better watch your step. How do I know this? We share a common bond; I too started as a stone mason (in Switzerland) just like he did - the cabinet makers and finish carpenters always looked like they were having more fun. Run a search for Stickley Design or cabinetry and you should find plenty.

From contributor D:

Stickley (or craftsman) design is a style unto itself. If you have a chance to read any of Stickley's writings you will find that what he was trying to accomplish a hundred years ago is very similar to what many people are trying to accomplish today. His philosophy was to provide the necessities in life in the simplest way possible.

Looking at craftsman furniture or cabinetry this quickly becomes evident. Most of the woodwork was built of quarter and rift sawn oak because it was abundantly available and the grain is fairly consistent and straight. However, they also made a lot of use of other woods like maple and cherry. Stickley believed in highlighting the wood's natural beauty - artificially 'aging' it. For oak and other woods high in tannins they used ammonia to fume the wood - there are some good alternatives to this today. For lighter colored woods, they developed a process using vinegar, iron filings and water for a finish.

The design is generally straightforward and simple. Straight lines and flat panels allow the eye to focus on details of construction rather than artificial adornments. Unique hardware was also a trademark.

There are a good many books on the subject that you should look at - most bookstores and libraries carry at least a few. There aren't many websites out there with good pictures of Stickley kitchens (because the company never really produced any), but search for 'craftsman style kitchen' and you'll have better luck. Also, look at craftsman furniture and adapt what you see to the cabinetry.

From contributor E:

Another good resource to look to for inspiration is American Bungalow and Arts and Crafts magazines. I used these magazines as a sales tool a couple of years ago to sell Craftsman/Mission style cabinetry for a modern bungalow being built by one of my builders.

If you do your homework and present your clients with choices from these sources, you will look well-informed and will have a good chance of making the sale. Good luck on this project, period kitchen cabinetry is always fun because they didn't really build kitchens back then, so you can put your own twist on the design.

From contributor F:

As an addition to contributor D's excellent post, Stickley (along with Greene and Greene, William Morris and many others) was a member/founder of the movement known as the Arts and Crafts Period. In large part, the movement was a response to the industrial revolution and the shoddy, soul-less, mass-produced goods that resulted. The design elements included through dovetails, butterfly keys, and more that required handwork (read: skill) to execute. This raised the level of work and made for meaningful work for the cabinetmakers.

Stickley started a community of shops for cabinetmakers, metalsmiths, jewelers and weavers, where the artisans and families lived in a semi-communal environment, and dedicated their skills to the group ability to execute fine work. Stickley even published a magazine "The Craftsman" that expanded his philosphy through good design - important lessons here for us in this line of work.

Consider this an opportunity to go to your local library or bookstore and do a bit of research. This style is becoming very popular, and will date quickly through overuse and bad execution. The irony is that the popularity of the style will warrant soul-less, mass produced copies of Arts and Crafts stuff everywhere, made by those with absolutely no comprehension of who Stickley was or the ideals of the movement.

From contributor G:

Looking back a hundred years to the arts and crafts era, it is easy to confuse the time relationships of the period. Gustav Stickley was publishing the 'Craftsman' magazine in the 1920's, whereas the arts and crafts movement began to flourish in the 1880's. Gustav had two older brothers, who went to England before 1900 to study arts and crafts techniques, and then came back to America to found some eight different companies manufacturing furniture under the Stickley name.

While Gustav is the recognized inheritor of trend, he was far from the origination of the style trend, and it is known that over two-hundred people contributed design to the Stickley family furniture industries. It may be that the key to understanding arts and crafts is not so much in the selection of wood as it is in understanding the construction techniques, based upon proven carcase engineering standards.

I find this quote from Gustav Stickley most endearing:

ďThe plea which THE CRAFTSMAN wishes to make is for intelligent labor which meets a practical need and which is also productive of beauty; which is wiser than play because it includes the element of play and yet leads to results; is more lasting in effect than work unrelated to life because it is the result of enlightened purpose, and thus is a part of general progress. What we plead for is discriminating labor, not mere slavery or unthinking play. It is productive work beyond mere financial returns that we believe will carry the final benefit for the human race."

From contributor A:

A big reason that Gustav Stickley is credited with being the father of the arts and crafts movement is owing to his creation of the Craftsman publication. There were probably no fewer than 400 firms manufacturing similar product at the time, but his is the name you remember. He was in his day what Martha Stewart is in ours. There are a lot of good woodworkers out there - the ones who are really famous are famous for a reason, but that reason has usually more to do with a marketing department.

A favorite of mine from Gustav's era (and any other) is Rennie Mackintosh. Take a look at what he was doing when everybody else was doing this somber oak. He didn't have a marketing department. His entire estate sold for $136.40

From contributor G:

Again, I believe, the truth is in the construction techniques. An understanding of the source of the arts and crafts movement is interesting, in that early proponents from William Morris to Gustav Stickley were impassioned anarchists, who on principle alone would have stripped away the superfluous notions of earlier design. If you dissect the gaudiest furniture design, the simple bones of carcase technology are revealed - a skeleton of form and function.

From contributor H:

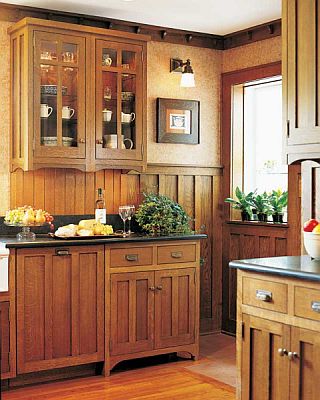

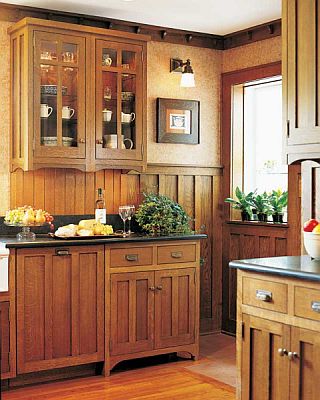

Here is an example from the Crownpoint Cabinetry website.

Click here for full size image

From the original questioner:

Thanks everyone. It gives me a good idea of what to shoot for.

From contributor C:

This has been one the most interesting posts I have read. Do you think the guy would have appreciated Frameless design? I have been thinking of doing a project that would include the same style of door but inset frameless.

From contributor G:

Point in fact - the picture of Crownpoint's cabinetry is not a true structural representation of arts and crafts construction technique. Arts and Crafts does not present form without function. A face frame would not have been utilized; the valanced bottom rail of the upper cabinets would have been one piece; the drawers would show between a webframed structure substrating the countertop; and the base is all wrong. But the picture is totally representative of semi-custom production cabinetry. Note the lack of continuity that is inherently derived from the 'box by box' product and production engineering concepts.

From contributor C:

So are you saying that frameless could be a representation of Arts and Crafts, with the caveat that the appropriate principles are adhered to and material is in line with traditional work selections?

From contributor H:

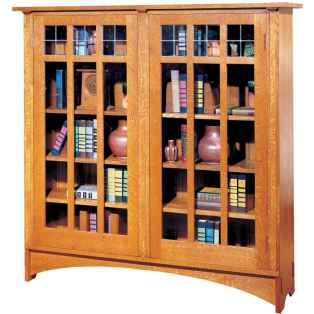

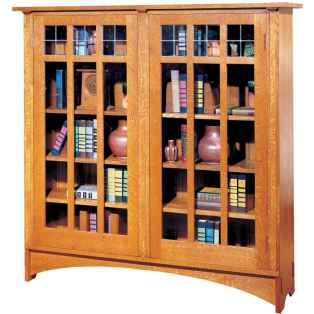

Is this a better representation of Stickley? I am not saying that Crownpoint makes a perfect interpretation of arts and crafts style furniture. Each design, including the one from Crownpoint, is just an interpretation. All I am presenting here was an answer to the original post. By the way, this picture is from the Stickley Furniture website.

Click here for full size image

From contributor F:

To design without knowledge of history is to officially "not get it." The fact is today's Stickley Furniture is Stickley only in name, and it simply doesn't embody the design principles, construction methods or philosophical depth that Gustav and others incorporated into their work and lives.

If one doesn't go back to the core or original, then one's interpretation of an interpretation, of another's interpretation of someone else's interpretation ends up far from the mark. Then you have the soul-less mass produced thing - the precise end Stickley and his contemporaries worked so hard to avoid.

The beauty of this forum is that one can choose from any level of interest offered. The original questioner may well just take his plywood and Oak and make square edge doors with vertical flat panels and call it Arts and Crafts and get by. Or he may do some research and find that he can incorporate some nice details and use the materials better than straight cabinets, and attract a higher level of customer. He could even go so far as making great reproductions of the style and ensuring his own secure future as successful woodworker. It's all possible.

From contributor I:

Just want to throw in a link between design and cost. If the customer has a low budget then I vote for "The original questioner may well just take his plywood and Oak and make square edge doors with vertical flat panels and call it Arts and Crafts and get by". If the project requires the history lesson and justification of what is truly "Stickley", and the execution is appropriate, then the price should be exorbitant. Don't give them more than they're paying for.

From contributor G:

An understanding of carcase engineering is key to the arts and crafts aesthetic. Carcase engineering resolves the construction issues of building a box from solid wood, where expansion and contraction eventually knocks the box apart. Unfortunately, this picture of a Stickley factory bookcase is not representative of what Stickley would have built. The example shows plywood panel sides and lipped doors. There is no webframe to substrate the top, and the strip of wood protruding from under the doors should have been an extension of the lower shelf, not a tacked on afterthought. The corbels are laughable.

With carcase engineering, form follows function with structure providing the aesthetic.

From contributor C:

If frameless is executed appropriately do you think it can be called Arts and Crafts/Stickley? It seems like it has all the right principles - straightforward construction, no face frame, etc. So what do you think?

From contributor G:

No. Frameless construction does not provide the structural integrity of carcase engineering. Yes - you can you build a set of frameless kitchen cabinets with an arts and crafts aesthetic. Or, you can build a set of kitchen cabinets utilizing carcase engineering, and derive full benefit of the arts and crafts aesthetic, with no recriminations. The concept of frameless is a misnomer of cabinet engineering, designed as a knock-down for easy container shipment to a gullible American market. Sadly, the competition spawned a denigrating evolution in American manufacture; not because it was better, just cheaper. But, today, it is not cheaper. Modern machines require modern materials. The actual cost of building with value-added materials has risen well beyond the cost of building with the random lengths and widths of wood.

From contributor B:

Maybe the base is all wrong because thatís a dishwasher. I wonder how Gustav and his brothers did their dishwasher panels. It seems to me that function was and is the foundation, and form follows. Kitchens have to function. I think the Stickleys and all the rest would have deviated from any rule or design criteria to allow function, and just like everything else, function evolves. A craftsman makes it bring form with it. Obviously you can't always make kitchen or bath cabinetry with the same features as a free standing piece of occasional use furniture. You have to apply the function and form rule to business also.

From the original questioner:

I went to the interview and he was more interested in the basic look of the Stickley design and not as much as the form. He really liked the q-sawn oak look with the flat panels. He is interested in keeping the cost down so a true carcass style piece of furniture cabinetry is probably out of the budget. Thank you for your input. It was all helpful, including the history lesson.

The comments below were added after this Forum discussion was archived as a Knowledge Base article (add your comment).

Comment from contributor J:

One of the primary characteristics of Stickley and Mission furniture is attention to the vector mechanics involved in daily furniture use. In all of the older pieces the design is intended to make the furniture as strong as possible (notice the boards on the sides of the chair seats and the through tenons on door frames.) The furniture was designed to handle daily stress very well for many years. I believe quartersawn wood was used because it doesn't warp.