Question

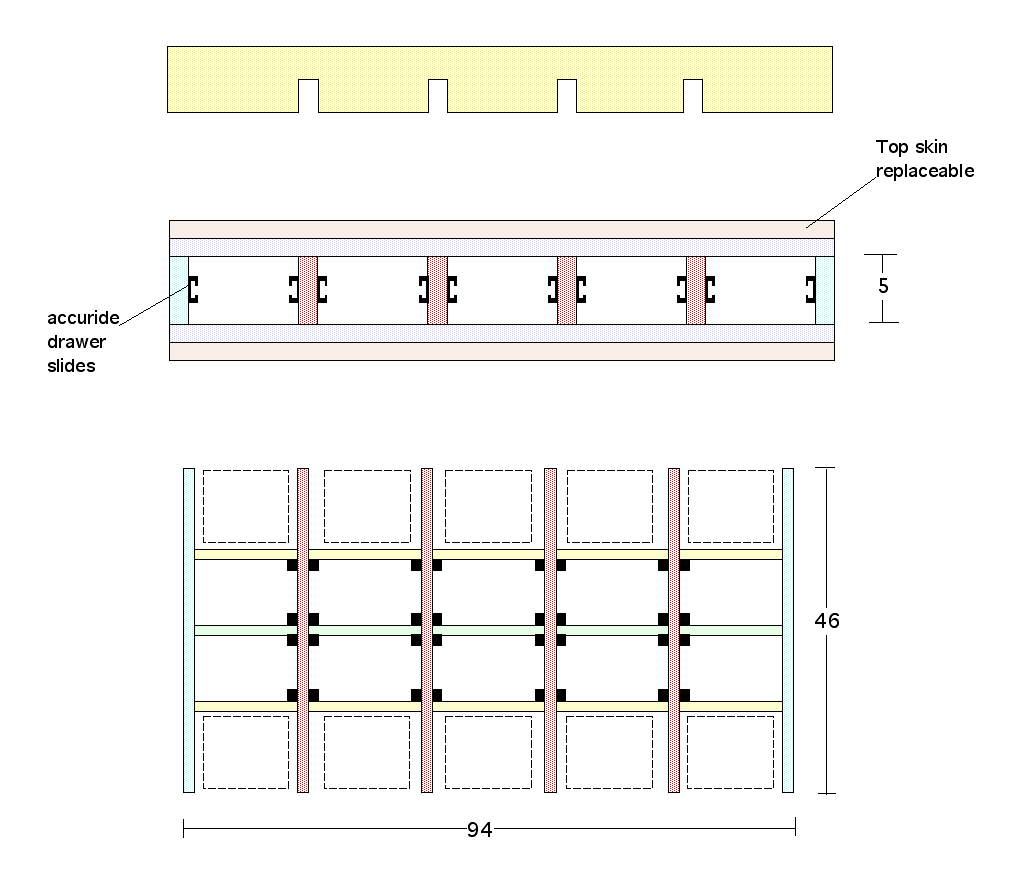

We do most of our assembly on scissorlift work benches. They have a 36 inch range of height and start about 8 inches off the floor. I would like to add a 4 x 8 surface for assembling cabinets that is as flat as possible. I am thinking this needs to be developed as a torsion box. I want to keep the overall height fairly minimal so that the dropped position of table surface isn't much more than 15 inches from the floor.

I would also like to integrate drawers into this structure but I don't want to compromise the flatness of the table.

The outermost layers would likely be melamine on MDF. The drawer slides would be something like an un-handed Accuride 3834. This way we could periodically flip the table if needed and still use the drawer boxes.

I've never built a torsion box like this before. My thinking is that the notches would start out a little bit loose, then be tightened up with some corner blocks. How does this idea sound? Any suggestions about how to keep the surface flat? Any suggestions for material?

Forum Responses

(Cabinetmaking Forum)

From contributor B:

Cool... How much larger is this than the top of the scissors lift? My gut reaction is that you'll want a ply material of some sort for the skeleton of your torsion box. Repeated loading of the outer sections of the work surface will deform the structure over time, I would think. Also, the notches should be as tight as you can make them; you want the intersecting pieces transferring the stresses to each other as much as possible, rather than through glue-joints and fasteners. It should make cabinet assembly a lot more gentlemanly!

I would ditch the drawer, as I see that as compromising the whole idea of the torsion box concept.

I don't waste time doing all that notching for the frame. Long strips with butt jointed cross members just stapled to hold the frame together is all you need. It's the skins that hold it all together. The staples are just to keep the frame together until the skins are on. Glue both skins at the same time.

Kirby and Horner are your best sources of tech help. Everyone else's process I've seen just adds more work to the whole torsion box. It's supposed to be simple, fast, lightweight, strong and flat. The lightweight depends on your frame material of course. MDF is fine if you want heavy.

You can flex it a little, but for the most part it's heavy, flat and cheap. I keep 3 positioned in an L shape just off the saw outfeed.

I have been working for 25 years on a table with a core of basswood 5/16" x 3 1/2" strips about 4" on center and skins of 1/4" luan plywood with hpl surfaces. It sits on supports within 16" of the ends and 8" from the edges. If your support is smaller you may need to add strongbacks or make the box a little thicker. Mine is a little shabby from errant sawcuts and mallet blows, but still serviceable and flat overall, and can be moved by one person easily, probably 70 lbs or so.

I have found it a little easier to assemble a core of halflapped continuous strips than stapling numerous individual pieces. The hardest part is making the first table flat. Mine was second generation, clamped with cauls to a torsion box that was assembled on a 3x6 cast iron machinist's setup table. After that it is easy to breed more with the "beast with two backs" technique. If you want to screw to your worktop you will want thicker skins, in which case you can go with larger spacing in the core grid. The core merely transfers shear stresses to the skins, so tight joinery in the core is not important, just sufficient glue surface to keep the skins together. If you are intent on drawers, you might support a proper torsion box on top of a timber and ply subframe, incorporating voids for your drawers, though that would be running up against your 15" min. height.