Question

I installed a wall unit consisting of Macassar ebony boxes with mahogany doors three weeks ago - veneer over MDF. The finish is beginning to develop checks along the grain pattern. This is with the ebony only and not the mahogany. The finish consisted of a one coat of Bullseye Sealcoat,crystalac grain filler, and Sherwin Williams nitrocellulose lacquer. I have finished a lot of ebony before without the crystalac without any problems so I tend to suspect the crystalac which was applied heavier to the ebony. The checks appear slightly whitish as though the lacquer cracked? I realize ebony can be slightly oily and the piece is in a drier climate than my shop, but that is nothing new as I've finished ebony many times in the past with no problem. I'm afraid the real answer I'm after is what would be the least messy way to strip off the finish.

Forum Responses

(Finishing Forum)

From contributor J:

How was the veneer applied? The first thing I suspect when this happens is not the finish itself but the glue and pressing of the veneer. Contact adhesive and a J roller are a recipe for failure every time. Are the mahogany doors veneer as well, glued and pressed the same as the ebony?

If the substrate moved rather uniformly, then the finish would be stressed uniformly and probably not crack easily. The problem we have is when the finish has a pre-existing crack (not too uncommon in some veneer that is of medium or low quality - lower cost often). Now, when the veneer shrinks just a bit with the exposure to low interior wintertime humidities, rather than shrink all over, the shrinkage will be concentrated in the crack and then this concentrated stress cracks the finish.

The cure is to purchase only the best veneer (manufacturing techniques are the best, that is), minimize moisture changes after finishing, and use the most flexible finish possible. (I also think that a thicker finish (several coats) can absorb stress better, but have not seen others adopt or accept this concept. There seems to be a trend to thinner finishes, which makes cracking more likely).

I had this exact problem three times on my 15 years - two times on veneered maple on columns and another time on plain sliced oak, contact cemented onto white melamine in the middle of winter, then brought into a hot Manhattan apartment when I was done. The cabinet maker actually blamed me for it and I took a $4,000 hit on it.

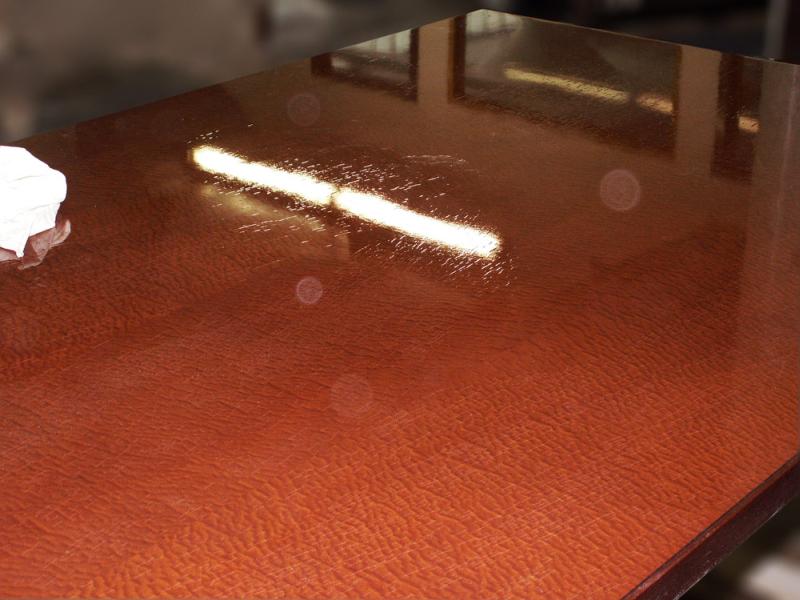

As you can see in this picture and the next the checks are white around the edges. In my experience they will always be white whether it’s the veneer or the finish failing. The only way to tell is to take it back down to raw wood and use a good magnifier. On this table the checking was only in the topcoat layer, the sealer build coat was intact.

Here is a close-up view. Anytime contact cement is used in veneer work I would be very concerned.

This table was veneered in a heated veneer press using urea formaldehyde glue. When the old finish was completely removed there were no checks in the veneer at all. I refinished it in a high gloss and it looked beautiful.

In the picture you presented, the number of cracks is huge and if we total up all the small cracks going across the grain, we see that there has been a lot of movement (or stress development) overall. The source of such movement could certainly be the elastic substrate coated with a rigid finish and then the substrate moves. (Analogy: Think of coating a rubber band with an inflexible coating, letting the coating dry, and then stretching the band a little bit.)

Incidentally, I can show you a veneer or solid wood surface that has lots of little checks (seen when the RH is real low), but because the RH is not real low it is impossible, even with 15x magnification, to see them. They close up tightly. I have also seen veneer that had finish cracks only on one side (the loose side). This was seen when the veneer was reversed face-to-back, such as when book-matching. What do you think? One other comment. I have seen cases that looked like your photo and at each crack there was a slight raised area right at the crack. Have you seen this? Any idea on a cause?

It is my thought that the cause of such raising is that the substrate is expanding, while the rigid finish cannot, so eventually the finish fails and lifts up to accommodate the larger substrate. (If the substrate were shrinking the finish would develop gaps).

Modern catalyzed finishes are very brittle and prone to checking on their own even when applied to a non-wood substrate. I would get in touch with chemists from a couple of the large finish companies and they can give you a better insight as to how this occurs.

From my experience CV is the worst culprit (which includes many pre-cat lacquers which are just CV hybrids) and you can cause checking 3 different ways:

1. Cold checking: If the finish drops below 65 degrees anytime within 48 hours of spraying.

2. Over catalyzation: Some finishers like to double the catalyst because it makes the CV dry faster in dusty environments.

3. Exceeding the max dry film thickness: Many shops use Kremlin air assisted guns these days and they pump out a lot of material fast. I have seen guys apply over 12 mils wet in one pass using this equipment.

I hope this helps Gene. I am just a finisher not a chemist and have found it better to talk to the chemist rather than the salesman when it comes to issues such as these.

Most coatings (there are exceptions) when cracked show up as white lines even when the veneer is not checked, as the light refraction has been broken by the break. Just like a crack in a piece of glass, the light cannot pass through and the eye sees this as (a white line in coatings) a dark line in glass. If the crack is repaired with an adhesive that has a similar light refraction index as the glass (or crystal) the break line virtually disappears as the light will pass through the glass and adhesive at the same rate.