Question

One of my customers is having a problem with this door. It was built out of car-decking material by one of the carpenters. It has rollers at the top that travel on a track. The bottom of the door is grooved to slide over a track on the floor at left side.

The door that the carpenters produced is warped too badly to use the track at the bottom. He would like us to build him a new one. My initial idea is to produce individual staves out of ripped and re-laminated lumber. We do this all the time for cabinet doors and can produce dead straight sticks with this method.

I am thinking about hanging the individual staves kind of like a curtain. What I am stuck on is how to join the individual staves to each other throughout the width of the door. Would a cable through the middle be pliable enough to allow individual staves to move without warping the whole system of staves?

Forum Responses

(Architectural Woodworking Forum)

From contributor M:

You don't say what size, but we would either vacuum bag thin chamfered boards on a solid engineered billet, or edge glue engineered stiles and v-groove on the router after. Wood species or look might be the final determining factor. If this is an interior application both sides, which it appears, I don't think any other treatment is needed. Sealing top and bottom is critical as usual.

Typically the bottom of the door has a plow that receives a short length of u-shaped metal mounted to the wall by the opening that keeps the door from swinging in or out, scraping the wall, smashing fingers, etc. This keeper is also sometimes a bearing wheel in larger doors - like real barns. This plow can also be stopped with hidden blocks to keep the door from running off the end of the track in either direction and keeps the pull from hitting the jamb. Better quality hardware will also provide stops as well as swing control. There is no need for track on the floor.

In the case of undesirable materials (from a construction standpoint) like barn wood, we go thinner on the plank faces. Usually 1/4" or 3/8". If budget permits, it's nice to miter the outside planks into the edges to give the appearance of solid planks.

A lot of the old houses here have the ledge type doors. Most of them are still straight. I think that is a possibility for smaller or sliding doors like the questioner has. Of course the old timers had better wood to use.

This door with breadboard ends is a different technique. These are solid wood with the verticals stub tenoned and doweled into the breadboard. The planks are splined together but not glued so they can shrink or grow a little. For tall doors in this style we usually use stave cores for the planks.

These doors were made to look like they were built of individual 4" to 6" wide v-groove boards. They were 3/4" thick by typically 18" to 24" wide and 26" to 32" high... so a lot smaller than a house door. However, the plan should still work.

The trick was to make the door blank as one full size solid wood flat 3/4" thick panel by edge gluing individual boards together, just as though you were making the blank for a raised panel. After the blank was made, I created the v-grooves slightly off line from the glue lines. These v-grooves were about 1/4" deep.

I then ran the door panel over the table saw with a very thin blade. The fence was positioned to cut a slot about 3/4 of the way through the 3/4" thick door slap, exactly lined up at the deepest v-point of the v-grooves. Looking at the slab after these slots were created, you maintained the v-groove appearance even though there was a thin slot running down the length at the center of each v-groove. This was the first step.

The second step was to repeat the process on the back of the panel, with the V-grooves on the back offset from those on the front by about 1/4". The result was that the slots cut 3/4 of the way through from the front were about 1/4" away from the slots cut 3/4 of the way through from the front of the door, in effect creating an accordion bellows type of effect. This created individual boards between each pair of v-groove cuts that could expand and contract individually. The pairs of front to rear slots (offset from each other by about 1/4") kept the entire slap from cupping or warping and each "board" now worked independent of the others. This of course made a very weak panel that was somewhat like our modern wacky wood when picked up. The final step was to put an upper and lower 1/2" x 2" stretcher across the back face of the door.

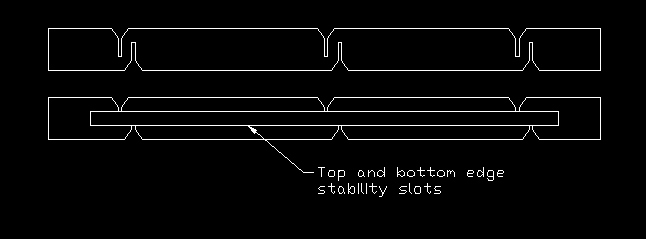

Now this stretcher is where a change in the construction would have to be made. Obviously you can't have stretchers on the back of the door. Instead of the stretchers you could machine a 2" deep slot in the top and bottom edges of the door. Insert either wood or metal and fix it in place with a doweled screw at either end. This should hold the door flat and force any expansion or contraction to take place within the doubled up accordion slots, holding the door flat and at a constant width.

Contributor J, those are some handsome doors.

Contributor B, that is an interesting premise. More so since it actually works.

There could be a bunch of reasons the original door warped. I'm putting my money on moisture migration from one or more staves. At the very least I will send the customer all these inputs. That way he won't think I just make this stuff up.